BBC

BBCIt was the wedding of the daughter of a Nepalese politician that first angered Aditya. The 23-year-old activist was scrolling through his social media feed in May, when he read complaints about how the high-profile marriage ceremony sparked huge traffic jams in the city of Bhaktapur.

What riled him most were claims that a major road was blocked for hours for VIP guests, who reportedly included the Nepalese prime minister.

Though the claim was never verified and the politician later denied that his family had misused state resources, Aditya’s mind was made up.

It was, he decided, “really unacceptable”.

Over the next few months he noticed more of what he saw as extravagances, posted on social media by politicians and their children – exotic holidays, pictures showing off mansions, supercars and designer handbags.

Saugat Thapa, a provincial minister’s son, posted a photograph that went viral. It showed an enormous pile of gift boxes from Louis Vuitton, Cartier and Christian Louboutin, decorated with fairy lights and Christmas baubles and topped with a Santa hat.

Instagram / sgtthb

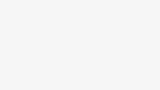

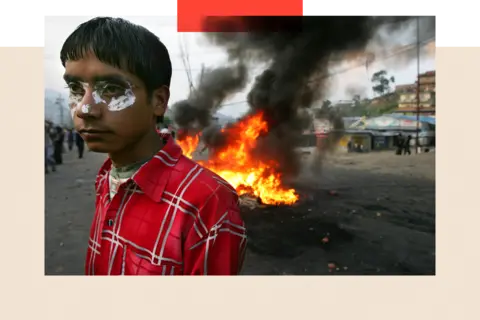

Instagram / sgtthbOn 8 September, determined to fight what he saw as corruption, Aditya and his friends joined thousands of young protesters on the streets of the capital Kathmandu.

As the protests gathered pace, there were clashes between demonstrators and police, leaving some protesters dead.

The following day, crowds stormed parliament and burned down government offices. The prime minister KP Sharma Oli resigned.

In all some 70 people were killed.

Sunil Pradhan/Anadolu via Getty Images

Sunil Pradhan/Anadolu via Getty ImagesThis was one part of a fervour for change that has swept across Asia in recent months.

Indonesians have staged demonstrations, as have Filipinos, with tens of thousands protesting in the capital Manila on Sunday. They all have one thing in common: they are driven by Generation Z, many of whom are furious at what they see as endemic corruption in their countries.

Governments in the region say there is a risk of the protests spiralling into unacceptable violence. But Aditya, like many demonstrators, believes it is the start of an era of newfound protester power.

He was inspired by the protests in Indonesia, as well as last year’s student-led revolution in Bangladesh and the Aragalaya protest movement that toppled Sri Lanka’s president in 2022, and he argues that all stand for the same thing: the “wellbeing and development of our nations”.

“We learnt that there is nothing that we – this generation of students and youths – cannot do.”

Backlash against ‘nepo kids’

Table of Contents

- 1. Backlash against ‘nepo kids’

- 2. Harnessing TikTok and AI

- 3. Political solidarity across nations

- 4. Deaths, destruction – now what?

- 5. Okay, here’s a breakdown of the provided text, focusing on key themes, Gen Z’s role, and the impact of technology. I’ll organize it into sections for clarity.

- 6. Gen Z in Asia: Driving Change Through Mass Protests

- 7. The Rise of a New Activism: Understanding Gen Z’s Role

- 8. Key Drivers of Gen Z Protests in Asia

- 9. Case Studies: Gen Z-Led Protests Across Asia

- 10. 1. Thailand: Pro-Democracy Movement (2020-2021)

- 11. 2. Hong Kong: Anti-Extradition Bill Protests (2019)

- 12. 3. Indonesia: Rejection of Controversial Laws (2019-2020)

- 13. 4. Philippines: Opposition to Red-Tagging and State Violence (Ongoing)

- 14. 5. South Korea: Addressing Gender Inequality and Social Issues (Ongoing)

- 15. The Role of Technology and Social Media

- 16. Challenges and Risks Faced by Gen Z Activists

- 17. Benefits of Gen Z Activism

- 18. Practical Tips for Supporting Gen Z Activists

Much of the anger has focused on so-called “nepo kids” – young people perceived as benefitting from the fame and influence of their well-connected parents, many of whom are establishment figures.

To many demonstrators, these “nepo kids” symbolise deeper corruption.

Some of those targeted have denied these allegations. Saugat Thapa said it was “an unfair misinterpretation” that his family was corrupt. Others have gone quiet.

But behind it all is a discontent over social inequality and a lack of opportunities.

PRAKASH MATHEMA/AFP via Getty Images

PRAKASH MATHEMA/AFP via Getty ImagesPoverty remains a persistent issue in these countries, which also suffer from low social mobility.

Multiple studies have shown that corruption reduces economic growth and deepens inequality. In Indonesia, corruption has been a serious impediment to the country’s development, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Since the start of the year, demonstrations have been held there over government budget cuts and, among other things, worries over economic prospects amid stagnating wages. In August, protests erupted over lawmakers’ housing perks.

Online hashtags circulated – #IndonesiaGelap (Dark Indonesia) and #KaburAjaDulu (Just Run Away First) – urging people to find opportunities elsewhere.

Photo by ARUN SANKAR/AFP via Getty Images

Photo by ARUN SANKAR/AFP via Getty ImagesZikri Afdinel Siregar, a 22-year-old university student living in North Sumatra in Indonesia, protested earlier this month, angered at local lawmakers receiving large housing allowances of 60 million rupiah (£2,670) per month, roughly 20 times the average income.

Back at home in the Riau province, Zikri’s parents have a small rubber plantation and do farm work on other people’s land, earning them four million rupiah (£178) a month.

He has been working as a motorcycle taxi driver to help cover his tuition fees and living costs.

“There are still many people who have difficulty buying basic necessities, especially food, which is still expensive now,” he says.

“But on the other hand, officials are getting richer, and their allowances are getting higher.”

Ezra Acayan/Getty Images

Ezra Acayan/Getty ImagesIn Nepal, one of the poorest countries in Asia, young people have expressed similar disillusionment at what they see as an unfair system.

Two years ago, in a case that shocked the nation, a young entrepreneur died after setting himself on fire outside parliament.

In his suicide note, he blamed the lack of opportunities.

Harnessing TikTok and AI

Days before the protests began in Nepal, the government announced a ban on most social media platforms for not complying with a registration deadline.

The government claimed it wanted to tackle fake news and hate speech. But many young Nepalese viewed it as an attempt to silence them.

Aditya was one of them.

He and four friends hunkered down in a library in Kathmandu with mobile phones and computers, and used AI platforms ChatGPT, Grok, DeepSeek and Veed to make 50 social media clips about “nepo kids” and corruption.

Over the next few days they posted them, mostly TikTok which had not been banned – using multiple accounts and virtual private networks to evade detection. They called their group ‘Gen Z Rebels’.

The first video, set to the Abba song, The Winner Takes It All, was a 25-second clip from the wedding that had enraged Aditya weeks ago, featuring pictures of the politician’s family along with headlines about the wedding.

It ended with a call to action: “I will join. I will fight against corruption and against political elitism. Will you?”

Within a day it had 135,000 views, its reach boosted by online influencers who recirculated it along with other posts, according to Aditya.

Navesh Chitrakar / Reuters

Navesh Chitrakar / ReutersOther groups based in Nepal and abroad also created clips, and shared them using Discord.

The gaming chat platform has been used by thousands of protesters in Nepal, where they discuss next moves and suggest who to nominate an interim leader for the country.

In the Philippines too, more than 30,000 people have contributed to a Reddit thread known as a “lifestyle check” campaign, in which many post details about the rich and powerful.

Sunil Pradhan/Anadolu via Getty Images

Sunil Pradhan/Anadolu via Getty ImagesYoung people harnessing technology for mass movements is nothing new – in the early 2000s text messaging propelled the second People’s Power Revolution in the Philippines, while the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street in the 2010s relied heavily on Twitter.

What’s different now is the sheer sophistication of the technology, with the widespread use of mobile phones, social media, messaging apps and now AI making it easier for people to mobilise.

“This is what [Gen Zs] grew up with, this is how they communicate… How this generation organises itself is a natural manifestation of that,” says Steven Feldstein, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Political solidarity across nations

Technology has also brokered a sense of solidarity among protesters in different countries.

A cartoon skull logo popularised by Indonesian demonstrators has been adopted by Philippine and Nepalese protesters too, appearing on protest flags, video clips and social media profile pictures.

The hashtag #SEAblings (a play on siblings in South East Asia or near the sea) has also trended online, as Filipinos, Indonesians and other nations express support for one another’s anti-corruption movements.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is true that Asia has previously seen similar waves of political solidarity across the region, from the Myanmar and Philippine uprisings in the late 1980s to the Milk Tea Alliance that began in 2019 with the Hong Kong demonstrations, according to Jeff Wasserstrom, a historian at the University of California Irvine. But he says this time it is different.

“[These days] the images [of protests] go further and faster than before, so you have a much bigger saturation of images of what’s happening in other places.”

Technology has also stoked emotions. “When you actually see it on your phone – the mansion, the fast cars – it just makes [the corruption] seem more real,” says Ash Presto, a Philippine sociologist with the Australian National University.

The impact is especially pronounced among Filipinos, who are among the world’s most active social media users, she adds.

Deaths, destruction – now what?

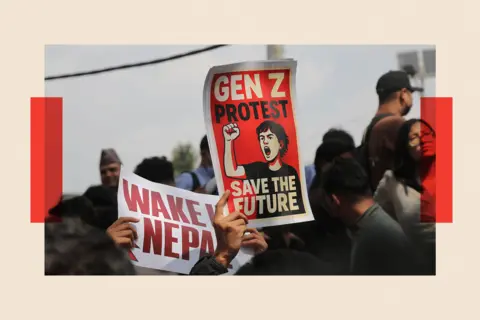

These protests have all led to serious consequences offline. Buildings have burnt down, homes have been looted and ransacked, and politicians have been dragged from their houses and beaten.

The damage to buildings and businesses alone is worth hundreds of millions of US dollars.

More than 70 people were killed in Nepal, and 10 people have died in Indonesia.

PRABIN RANABHAT/AFP via Getty Images

PRABIN RANABHAT/AFP via Getty ImagesGovernments have condemned the violence. Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto criticised what he called behaviour “leaning towards treason and terrorism … [and] destruction of public facilities, looting at homes”.

In the Philippines, President Ferdinand Marcos said protesters were right to be concerned about corruption, but urged them to be peaceful.

Meanwhile Philippine minister Claire Castro warned that people with “ill intentions [who] want to destabilise the government” were exploiting the public’s outrage.

Protesters, however, have blamed “infiltrators” for the violence and in Nepal’s case many claim that the high death toll was due to a heavy-handed crackdown by the police (which the government has said they will investigate).

BAY ISMOYO/AFP via Getty Images

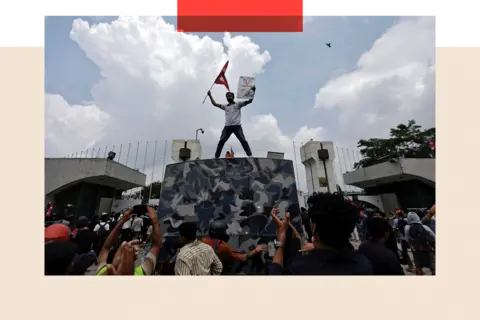

BAY ISMOYO/AFP via Getty ImagesAmong it all, governments have also acknowledged the protesters’ concerns and in some cases agreed to certain demands.

Indonesia has scrapped some of the financial incentives for lawmakers, like the controversial housing allowance, as well as overseas trips. And in the Philippines, an independent commission has been set up to investigate the possible misuse of flood prevention funds, with President Marcos promising there would be “no sacred cows” in the hunt.

The question now is, what follows the fury?

Navesh Chitrakar / Reuters

Navesh Chitrakar / ReutersFew digital-driven protests have translated to fundamental social change, observers point out – especially in places where problems like corruption remain deeply entrenched.

This is partly due to the leaderless nature of these demonstrations, which on the one hand helps protesters evade clampdowns – but also impedes long-term decision-making.

“[Social media] inherently is not designed for long-term change… you are relying on algorithms and outrage and hashtags to sustain it,” Dr Feldstein points out.

“[Change requires people to] find a way to change from a disparate online movement to a group that has a longer-term vision, with bonds that are physical as well as online.

“You need people to come up with viable political strategies, not just going with a zero-sum, burn-it-all-down strategy.”

Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Paula Bronstein/Getty ImagesThis was evident in previous conflicts, including in 2006 when Nepal’s millennials took part in a revolution that ousted the monarchy, following a Maoist insurgency and a decade-long civil war. But the country then cycled through 17 governments, while its economy stagnated.

The previous generation of Nepalese protesters “ended up becoming part of the system and lost their moral ground,” argues Narayan Adhikari, co-founder of Accountability Lab, an anti-corruption group.

“They didn’t follow democratic values and backtracked from their own commitment.”

But Aditya vows that this time will be different.

“We are continuously learning from the mistakes of our previous generation,” he says firmly. “They were worshipping their leaders like a god.

“Now in this generation, we do not follow anyone like a god.”

Additional reporting by Astudestra Ajengrastri and Ayomi Amindoni of BBC Indonesian, and Phanindra Dahal of BBC Nepali

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Okay, here’s a breakdown of the provided text, focusing on key themes, Gen Z’s role, and the impact of technology. I’ll organize it into sections for clarity.

Gen Z in Asia: Driving Change Through Mass Protests

Published: 2025/09/23 21:24:41 | Author: Omar Elsayed | website: archyde.com

The Rise of a New Activism: Understanding Gen Z’s Role

Across Asia, a powerful force is reshaping the political and social landscape: Generation Z. Born roughly between 1997 and 2012, this digitally native cohort is demonstrating a remarkable propensity for mass protests and activism, challenging established norms and demanding change. Unlike previous generations, their activism is often decentralized, fueled by social media, and focused on a diverse range of issues, from climate change and political reform to human rights and economic inequality. This article explores the key drivers behind this phenomenon, examines specific examples of Gen Z activism in Asia, and analyzes its impact.

Key Drivers of Gen Z Protests in Asia

Several factors contribute to the heightened activism of Asian Gen Z:

* Digital Native Status: Growing up with constant access to the internet and social media platforms like TikTok, Twitter (X), Instagram, and Telegram allows for rapid information dissemination, mobilization, and organization. This facilitates online activism and translates into offline action.

* Economic Precarity: Many Gen Z individuals face uncertain economic futures, grappling with youth unemployment, rising living costs, and limited opportunities. This fuels frustration and a desire for economic justice.

* Political Disillusionment: A perceived lack of depiction and responsiveness from traditional political institutions contributes to a sense of alienation and a willingness to challenge the status quo. This is especially pronounced in countries with limited political freedom.

* Exposure to Global Issues: The internet provides unprecedented access to information about global events, fostering a sense of interconnectedness and inspiring action on issues like climate crisis, racial justice, and gender equality.

* Influence of Social Movements: Global movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo have resonated strongly with Asian Gen Z, inspiring them to address similar issues within their own contexts.

Case Studies: Gen Z-Led Protests Across Asia

The impact of Gen Z activism is visible across the continent. Here are some notable examples:

1. Thailand: Pro-Democracy Movement (2020-2021)

The Thai pro-democracy movement, largely spearheaded by students and young activists, demanded reforms to the monarchy, a new constitution, and an end to military interference in politics. Social media played a crucial role in organizing protests, sharing information, and circumventing government censorship. Key demands included:

* Constitutional amendments to limit the power of the monarchy and military.

* Dissolution of parliament and fresh elections.

* Protection of freedom of speech and assembly.

* Addressing political repression and human rights abuses.

This movement, while facing meaningful government crackdown, demonstrated the power of youth-led protests in challenging authoritarian regimes.

2. Hong Kong: Anti-Extradition Bill Protests (2019)

While not exclusively Gen Z, young people were at the forefront of the massive anti-extradition bill protests in Hong Kong. these protests, initially sparked by a controversial extradition bill, quickly evolved into a broader movement demanding greater democracy and autonomy from China.Online organizing and the use of encrypted messaging apps were vital for coordinating protests and evading surveillance. the protests highlighted concerns about civil liberties and the erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms.

3. Indonesia: Rejection of Controversial Laws (2019-2020)

Indonesian students and young activists organized widespread protests against controversial legislation, including revisions to the criminal Code and a new labor law. These laws were perceived as undermining democratic principles, restricting freedom of expression, and weakening worker rights. Campus protests and street demonstrations were common,utilizing social media to amplify their message and mobilize support.

4. Philippines: Opposition to Red-Tagging and State Violence (Ongoing)

Filipino Gen Z activists are actively protesting against red-tagging (the practice of labeling individuals as communists or terrorists), state violence, and the erosion of human rights under the current governance. They utilize online campaigns and offline protests to raise awareness, defend activists, and demand accountability. The focus is on protecting freedom of expression and challenging authoritarian tendencies.

South Korean Gen Z is increasingly vocal about issues like gender inequality, sexual harassment, and the high cost of living. The #MeToo movement gained significant traction in South Korea, fueled by young women sharing their experiences of abuse. Protests and online activism are used to demand systemic change and challenge traditional patriarchal norms.

social media is undeniably the central nervous system of Gen Z activism in Asia. Platforms like:

* TikTok: Used for short-form video activism, raising awareness, and mobilizing support.

* Twitter (X): Facilitates real-time updates, information sharing, and organizing protests.

* Instagram: Used for visual storytelling, sharing personal experiences, and building communities.

* Telegram & Signal: Provide secure interaction channels for organizing and coordinating activities, particularly in countries with strict censorship.

* Facebook: Remains a significant platform for organizing events and reaching wider audiences.

These platforms enable rapid mobilization, bypass traditional media gatekeepers, and amplify marginalized voices. However, they also present challenges, including the spread of misinformation, online harassment, and government surveillance.Digital security and media literacy are thus crucial skills for young activists.

Challenges and Risks Faced by Gen Z Activists

Despite their energy and determination, Gen Z activists in asia face significant challenges:

* Government Repression: Many governments respond to protests with force, including arrests, intimidation, and censorship. Freedom of assembly is frequently enough restricted.

* Online Surveillance: Activists are often subjected to online surveillance and monitoring, potentially leading to harassment and persecution.

* Disinformation Campaigns: governments and other actors may launch disinformation campaigns to discredit activists and undermine their movements.

* Social Stigma: In some societies, activism is viewed negatively, and activists may face social ostracism or discrimination.

* Burnout and Mental Health: The constant pressure and emotional toll of activism can lead to burnout and mental health challenges.

Benefits of Gen Z Activism

Despite the risks, Gen Z activism offers significant benefits:

* Increased Political awareness: Raises awareness about vital social and political issues among both young people and the wider public.

* Greater Civic Engagement: Encourages young people to participate in the political process and become active citizens.

* Policy Changes: Can lead to concrete policy changes and reforms, addressing issues like climate change, human rights, and economic inequality.

* Empowerment of Marginalized groups: Provides a platform for marginalized groups to voice their concerns and demand justice.

* Strengthening of Democratic Institutions: Contributes to the strengthening of democratic institutions and the promotion of good governance.

Practical Tips for Supporting Gen Z Activists

* Amplify their voices: Share their content on social media and raise awareness about their campaigns.

* Provide financial support: Donate to organizations that support youth activism.

* Offer legal assistance: provide legal support to activists who are facing arrest or persecution.

* Promote digital security: Educate activists about digital security best practices.

* Advocate for policy changes: Lobby governments