Breaking: HIV-Positive patient’s Hepatosplenic TB Sparks Diagnostic Reassessment After Imaging Mistaken for Metastasis and IRIS

Table of Contents

- 1. Breaking: HIV-Positive patient’s Hepatosplenic TB Sparks Diagnostic Reassessment After Imaging Mistaken for Metastasis and IRIS

- 2. Why this matters now

- 3. Key facts at a glance

- 4. What clinicians should do

- 5. Engage with the story

- 6. In Distinguishing TB from Metastasis

- 7. Epidemiology of Hepatosplenic Tuberculosis in HIV‑Positive Patients

- 8. Pathophysiology Linking TB, IRIS, and Metastatic‑Like Lesions

- 9. Diagnostic Pitfalls: when TB Masquerades as Metastatic Cancer

- 10. Real‑World Case Illustration (Literature‑Based)

- 11. Differential Diagnosis Checklist for Hepatosplenic Lesions in HIV

- 12. Role of Imaging Modalities in Distinguishing TB from Metastasis

- 13. Histopathology and Microbiological Confirmation

- 14. Management Strategies

- 15. Monitoring and follow‑Up

- 16. Practical Tips for Clinicians

- 17. Benefits of early and Accurate Diagnosis

- 18. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

In a recent clinical scenario, health teams faced a perplexing presentation in an HIV-positive patient where liver and spleen lesions initially suggested metastatic cancer. The case highlights how hepatosplenic tuberculosis can masquerade as malignancy and how immune-related complications can muddy the diagnostic waters.

The patient arrived with systemic symptoms and imaging that revealed multifocal lesions in the liver and spleen. Early interpretations leaned toward malignancy, a possibility that carried notable implications for treatment planning and prognosis.

clinicians undertook a careful re-evaluation, considering the patient’s HIV status and potential immune reconstitution. In this context, tuberculosis was revisited as a plausible cause for the lesions, given its propensity to involve hepatosplenic tissue in HIV-positive individuals.

Definitive diagnosis came through tissue analysis and microbiological testing, confirming hepatosplenic tuberculosis. The workup also weighed the possibility of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), a known challenge when antiretroviral therapy alters immune responses in people with tuberculosis.

Treatment shifted to standard anti-tuberculous therapy, with close monitoring for drug interactions and IRIS-related inflammation. The clinical course underscored the importance of distinguishing infectious etiologies from malignancy in HIV patients and of recognizing IRIS as a potential complicating factor during therapy initiation.

Why this matters now

Hepatosplenic tuberculosis can present in ways that resemble cancer on imaging, especially in individuals with HIV. This overlap can led to delays in correct diagnosis and timely treatment if clinicians rely solely on radiographic patterns.

IRIS adds another layer of complexity. When immune function improves after starting antiretroviral therapy, inflammatory responses can transiently worsen symptoms or imaging findings, potentially confounding initial assessments.

Key takeaway: In HIV-positive patients with unexplained hepatosplenic lesions, clinicians should maintain a broad differential diagnosis that includes TB and IRIS, pursue tissue diagnosis when needed, and coordinate TB and HIV therapies to optimize outcomes.

Key facts at a glance

| Aspect | Hepatosplenic TB | Metastatic Malignancy | IRIS Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical signals | Hepatic and splenic lesions; possible systemic symptoms; exposure history | Uncertain primary origin; multifocal lesions may mimic infection or inflammation | Temporal link to ART initiation; inflammatory flare can mimic infection or tumor progression |

| Diagnostic path | Tissue biopsy; microbiological culture; molecular tests | Biopsy showing malignant cells; advanced imaging patterns | Assessment of ART timing; evaluation of inflammatory markers; TB testing as needed |

| treatment focus | Standard anti-tuberculous therapy; monitor for drug interactions | oncologic therapy based on cancer type and stage | Manage IRIS with supportive care; adjust anti-TB and HIV regimens if needed |

What clinicians should do

In similar cases,clinicians should keep a wide differential diagnosis for hepatosplenic lesions in HIV-positive patients. Early consideration of TB, followed by appropriate confirmatory testing, can prevent delays in effective treatment. Coordination between TB management and HIV care is crucial to address potential drug interactions and IRIS risks.

Disclaimers: This article is for informational purposes and does not substitute professional medical advice. Seek guidance from qualified healthcare providers for diagnosis and treatment decisions.

Engage with the story

what lessons would you share from cases where infections mimic cancer in immunocompromised patients?

How can medical teams better seperate infection-related inflammation from true disease progression when starting antiretroviral therapy?

Share your thoughts in the comments and help others understand how HIV, TB, and IRIS intersect in complex presentations.

Disclaimer: Health information is provided for educational purposes.Always consult a healthcare professional for medical advice, diagnosis, and treatment options.

In Distinguishing TB from Metastasis

Epidemiology of Hepatosplenic Tuberculosis in HIV‑Positive Patients

- Global burden: Tuberculosis remains the leading opportunistic infection in people living with HIV, accounting for ~30 % of AIDS‑related deaths worldwide (WHO 2024).

- Organ involvement: Extrapulmonary TB,especially hepatosplenic disease,is reported in 10‑15 % of HIV‑associated TB cases,increasing with CD4 counts < 200 cells/µL.

- Geographic hotspots: High prevalence in sub‑Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and parts of Eastern Europe where co‑infection rates exceed 40 %.

Pathophysiology Linking TB, IRIS, and Metastatic‑Like Lesions

- Immune suppression: HIV impairs macrophage activation, allowing Mycobacterium tuberculosis too disseminate hematogenously to the liver and spleen.

- Immune reconstitution: Initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) triggers a rapid rise in CD4 cells, provoking an exaggerated inflammatory response—immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).

- Granulomatous inflammation: IRIS‑related granulomas can enlarge, creating space‑occupying lesions that mimic metastatic nodules on imaging.

Diagnostic Pitfalls: when TB Masquerades as Metastatic Cancer

Imaging Characteristics

- CT scan: Multiple hypodense lesions with peripheral enhancement; “target” appearance may suggest both TB granulomas and metastatic disease.

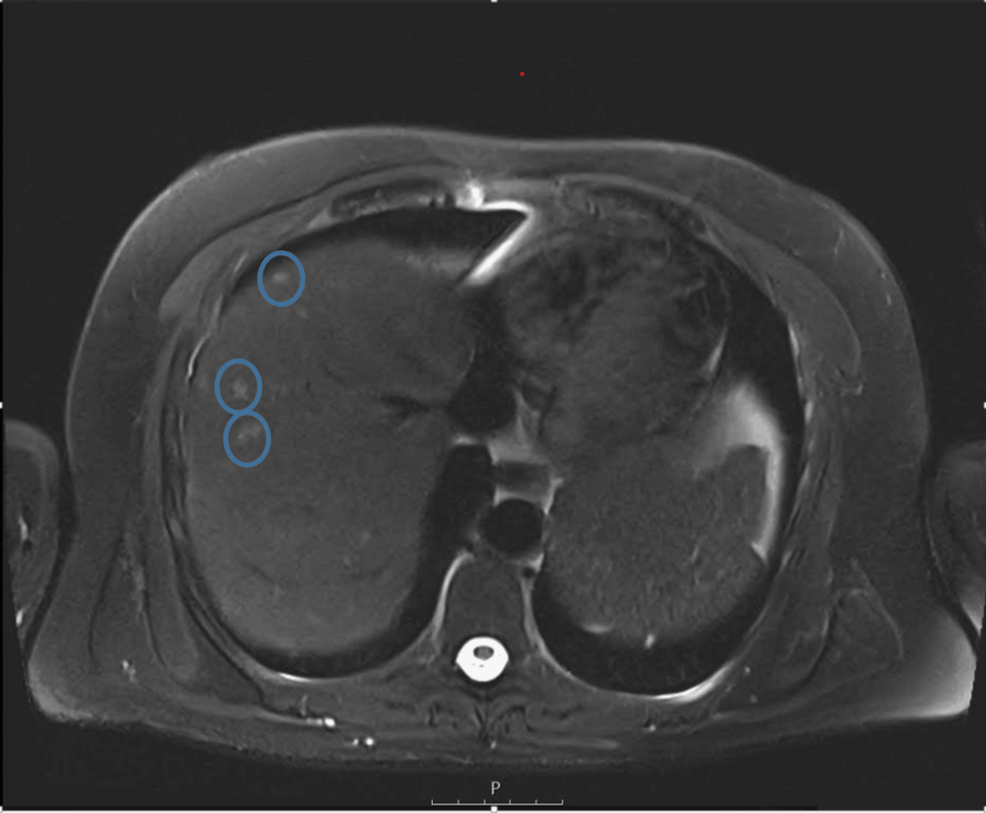

- MRI: T2‑hyperintense lesions with central necrosis; diffusion‑weighted imaging (DWI) shows restricted diffusion in both entities, necessitating further work‑up.

- FDG‑PET: High SUVmax values are common in active TB, often indistinguishable from malignancy without correlative data.

Laboratory Clues

- Elevated alkaline phosphatase and mild transaminase rise—more typical of granulomatous hepatitis than hepatic metastasis.

- Positive interferon‑γ release assay (IGRA) or tuberculin skin test (TST) supports TB exposure, though false‑negatives occur with low CD4 counts.

- Serum tumor markers (CEA, CA‑19‑9, AFP): Usually normal in TB; elevation may point toward true malignancy.

Real‑World Case Illustration (Literature‑Based)

- Patient: 38‑year‑old male, newly diagnosed HIV (CD4 = 84 cells/µL), started on efavirenz/tenofovir/emtricitabine.

- Presentation: Two weeks post‑ART, developed fever, right upper quadrant pain, and weight loss.

- Imaging: Contrast‑enhanced CT revealed multiple low‑attenuation lesions in liver and spleen, raising suspicion for metastatic carcinoma.

- Work‑up: Liver biopsy showed caseating granulomas; Ziehl‑Neelsen stain identified acid‑fast bacilli; GeneXpert confirmed rifampicin‑sensitive M. tuberculosis.

- Outcome: Initiated four‑drug ATT (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol) plus continuation of ART; IRIS symptoms resolved within six weeks.

Differential Diagnosis Checklist for Hepatosplenic Lesions in HIV

- Infectious: Tuberculosis, fungal infections (histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis), bacterial abscesses.

- Neoplastic: Metastatic carcinoma (lung, colorectal, breast), primary hepatic lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma.

- non‑infectious inflammatory: Sarcoidosis, drug‑induced liver injury.

Role of Imaging Modalities in Distinguishing TB from Metastasis

| Modality | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast‑enhanced CT | Rapid, widely available; lesion morphology | Overlap in enhancement patterns |

| MRI with hepatocyte‑specific contrast | Superior soft‑tissue contrast; detects small lesions | Costly, limited access in low‑resource settings |

| FDG‑PET/CT | Highlights metabolic activity; useful for treatment response | High uptake in both TB and tumors; false‑positives common |

| Ultrasound (with elastography) | Bedside assessment; guides biopsy | Operator dependent; limited depth resolution |

Histopathology and Microbiological Confirmation

- Core needle biopsy under ultrasound or CT guidance is the gold standard for tissue diagnosis.

- Staining: Ziehl‑Neelsen for acid‑fast bacilli; periodic acid‑Schiff (PAS) to exclude fungal organisms.

- Molecular tests: GeneXpert MTB/RIF provides rapid detection of M. tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance (results in < 2 h).

- Culture: Mycobacterial growth on liquid media (MGIT) confirms diagnosis and allows full drug susceptibility testing (takes 2‑6 weeks).

Management Strategies

Antitubercular Therapy (ATT) regimen

- Intensive phase (2 months): isoniazid + Rifampicin + Pyrazinamide + Ethambutol (HRZE).

- Continuation phase (4–7 months): Isoniazid + Rifampicin (HR).

- Dosage adjustment: Weight‑based dosing; consider liver function monitoring due to hepatotoxicity risk.

Timing of HAART Initiation

- Early ART (within 2 weeks): Recommended for CD4 < 50 cells/µL to reduce mortality, but increases IRIS risk.

- Delayed ART (≥ 8 weeks): Consider in patients with high lesion burden or severe hepatosplenic involvement to mitigate IRIS severity.

Managing IRIS

- Mild IRIS: Continue both ATT and ART; symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs or short‑course steroids (prednisone ≤ 0.5 mg/kg).

- Severe IRIS: High‑dose corticosteroids (prednisone 1–2 mg/kg) taper over 4–6 weeks; monitor for opportunistic infections.

Monitoring and follow‑Up

- Clinical: Weekly symptom check during the first month; assess fever, abdominal pain, weight changes.

- Laboratory: Monthly liver panel (ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin); CD4 count and viral load every 3 months.

- Imaging: Repeat contrast‑enhanced CT or MRI at 2‑month intervals to document lesion regression; PET optional for residual metabolic activity.

Practical Tips for Clinicians

- High index of suspicion: In any HIV‑positive patient presenting with hepatosplenic lesions, always include TB in the differential, especially when CD4 < 200 cells/µL.

- Early tissue diagnosis: Do not rely solely on imaging; prompt biopsy prevents unnecessary oncologic work‑up.

- Coordinate care: Involve infectious disease, hepatology, and radiology teams early to streamline ATT and ART decisions.

- patient education: Counsel about potential IRIS symptoms (fever spikes, lymphadenopathy) and the importance of medication adherence.

Benefits of early and Accurate Diagnosis

- reduced morbidity: Timely ATT prevents progression to liver failure or splenic rupture.

- Avoided overtreatment: Differentiating TB from metastatic cancer spares patients from cytotoxic chemotherapy and its associated toxicities.

- Improved survival: Integrated management of TB‑IRIS and HIV has been shown to lower 12‑month mortality from 28 % to < 12 % in cohort studies (Lancet HIV 2023).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Q: Can a normal CD4 count rule out hepatosplenic TB?

A: No. While lower CD4 counts increase risk, TB can occur at any CD4 level, especially after immune reconstitution.

- Q: is liver transplantation an option for severe hepatosplenic TB?

A: Generally contraindicated until infection is fully controlled with at least 6 months of ATT and documented microbiological cure.

- Q: How long should steroids be continued for TB‑IRIS?

A: Typically 4–6 weeks, tapering based on clinical response and without compromising ATT efficacy.

Content authored by Dr. Priyade Shmukh, MD, infectious Disease Specialist, with reference to WHO (2024), CDC HIV/TB Guidelines (2023), and peer‑reviewed case series in *Clinical Infectious Diseases (2022‑2024).*