Oral Anticoagulants Show Net Benefit in Patients with History of Intracranial Hemorrhage, but Increased ICH Risk Noted

Table of Contents

- 1. Oral Anticoagulants Show Net Benefit in Patients with History of Intracranial Hemorrhage, but Increased ICH Risk Noted

- 2. What are the key considerations when choosing between NOACs and warfarin for post-ICH anticoagulation in patients with AF?

- 3. AF Post-ICH Anticoagulation: An Ongoing Challenge

- 4. understanding the complex Interplay

- 5. Risk Stratification: identifying Vulnerable Patients

- 6. Timing of Anticoagulation Restart: A Critical Window

- 7. Choosing the Right Anticoagulant: NOACs vs. Warfarin

- 8. Monitoring and Management: Minimizing Risks

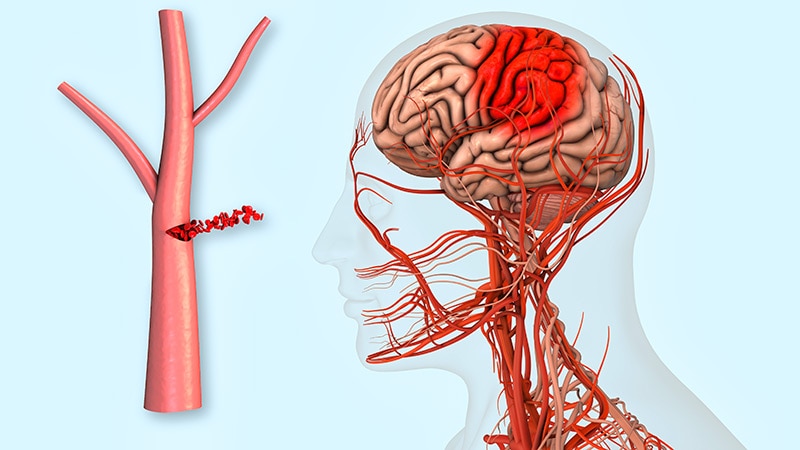

New York, NY – A recent meta-analysis published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology suggests that oral anticoagulants (OACs) offer a net clinical benefit for patients with a history of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), primarily by considerably reducing the risk of ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolism. Though, the study also highlights a notable increase in the risk of recurrent ICH associated with their use.

The analysis, which pooled data from four low-risk-of-bias trials, involved a cohort of predominantly White men (78.2 years of age, 38% women, 95% White). Follow-up periods in the included trials ranged from a mean of 0.53 years to a median of 1.9 years. The primary endpoint, net adverse clinical events, was a composite measure including ischemic stroke, systemic thromboembolism, nonfatal heart attack, cardiovascular death, recurrent ICH, and major extracranial bleeding.

among the oacs used in the analyzed trials, apixaban was the most common (65%), followed by edoxaban (15%), dabigatran (14%), rivaroxaban (4%), and warfarin (1%).

The findings indicate that OACs reduced the overall risk of net adverse clinical events by 31% (relative risk [RR], 0.69; 95% CI, 0.52-0.93). Crucially, they demonstrated a significant 76% reduction in ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolism (RR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.09-0.61), meaning that 8 patients would need to be treated to prevent one such event.Conversely, the study identified a more then threefold increased risk of recurrent ICH with OAC use (RR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.30-7.85),translating to a number needed to harm of 22,meaning 22 patients would need to be treated to observe one additional recurrent ICH event.

No important differences where observed between OAC users and non-users in rates of fatal ischemic stroke, fatal ICH, major extracranial hemorrhage, myocardial infarction, or cardiovascular death.

Researchers emphasized that this meta-analysis provides valuable insights for shared decision-making between clinicians and patients. “The magnitude of benefit and risk may differ across ICH subtypes and with the timing of oacs initiation, warranting further investigation through [individual patient data] meta-analysis,” the study authors stated, suggesting that future research should delve deeper into these nuances.

Limitations of the study include the lack of individual patient data, which precluded more granular analyses such as the timing of events. Furthermore, the number of included trials and participants was insufficient to detect effects on less frequent outcomes. All included trials were also open-label in design. Some authors reported receiving research funding and acting as consultants for pharmaceutical companies.

What are the key considerations when choosing between NOACs and warfarin for post-ICH anticoagulation in patients with AF?

AF Post-ICH Anticoagulation: An Ongoing Challenge

understanding the complex Interplay

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) represent two meaningful cardiovascular and neurological challenges. The intersection of these conditions – managing anticoagulation after an ICH in patients with AF – presents a particularly complex clinical dilemma.Balancing the risk of recurrent stroke due to AF against the risk of hematoma expansion or secondary hemorrhage with continued anticoagulation requires careful consideration and individualized patient management. This article delves into the nuances of post-ICH anticoagulation in AF, exploring current guidelines, emerging evidence, and practical approaches. Key terms include anticoagulation management, stroke prevention, intracerebral hemorrhage, atrial fibrillation, and secondary stroke risk.

Risk Stratification: identifying Vulnerable Patients

Accurate risk stratification is paramount. Not all patients with AF and ICH require the same approach to anticoagulation. Several factors influence the decision-making process:

ICH Severity: Larger hemorrhages generally warrant a longer pause in anticoagulation.

AF Subtype: Paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent AF impacts the urgency of resuming anticoagulation.

HAS-BLED score: this tool assesses bleeding risk, guiding the intensity of anticoagulation. A high HAS-BLED score doesn’t preclude anticoagulation, but necessitates careful monitoring.

CHA2DS2-VASc Score: This score evaluates stroke risk in AF patients. Higher scores indicate a greater need for anticoagulation.

Hematoma Expansion: Evidence of ongoing hematoma expansion influences the timing of anticoagulation restart.

Timing of Anticoagulation Restart: A Critical Window

The optimal timing for resuming oral anticoagulation (OAC) after ICH remains a subject of debate. Historically, a “wait and see” approach of several days to weeks was common. Though, recent research suggests earlier resumption might potentially be beneficial in select patients.

Early Restart (within 7 days): Studies like RESTART (Early versus Late Restart of Anticoagulation after Stroke) have shown that early resumption of OAC, guided by CT or MRI scans to rule out ongoing hemorrhage expansion, is associated with improved outcomes and reduced recurrent ischemic events.

Delayed restart (beyond 7 days): Reserved for patients with larger hemorrhages, significant hematoma expansion, or uncontrolled hypertension.

Individualized Approach: The decision must be individualized, considering the patient’s risk profile and imaging findings. A multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, cardiologists, and hematologists is highly recommended.

Choosing the Right Anticoagulant: NOACs vs. Warfarin

The choice between non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) and warfarin is another crucial consideration.

NOACs (Direct Oral Anticoagulants – DOACs): Apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban offer several advantages:

Faster onset and offset of action.

More predictable anticoagulation effect, reducing the need for frequent monitoring.

Potentially lower risk of ICH compared to warfarin (even though this is debated).

Warfarin: Requires regular INR monitoring and has a narrower therapeutic window. Though, it might potentially be preferred in patients with mechanical heart valves or severe renal impairment where NOACs are contraindicated.

Recent data suggests NOACs might potentially be favored in the post-ICH setting due to their more favorable safety profile and ease of management. Though, warfarin remains a viable option in specific clinical scenarios.

Monitoring and Management: Minimizing Risks

Regardless of the chosen anticoagulant, diligent monitoring is essential.

Regular Neurological Assessments: Monitor for signs of recurrent hemorrhage or neurological deterioration.

Blood Pressure Control: Strict blood pressure management is crucial to prevent hematoma expansion and secondary hemorrhage.