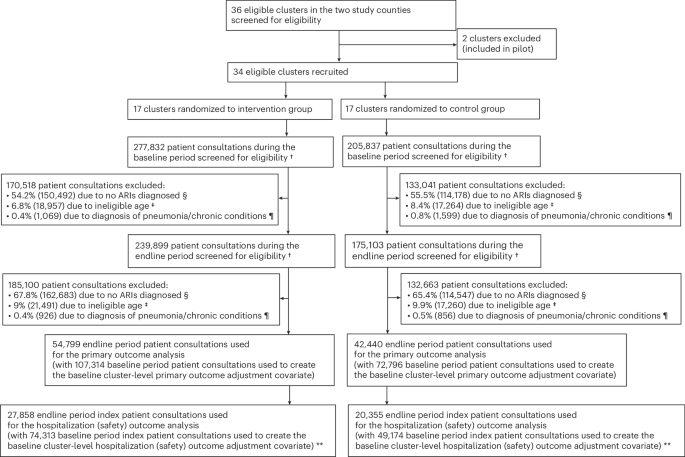

In rural healthcare settings, the over-prescription of antibiotics for acute respiratory infections has become a pressing concern. A recent cluster randomized trial has shed light on the effectiveness of a comprehensive antibiotic stewardship program in these regions. The study aimed to evaluate how such a program could impact antibiotic prescribing practices and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Many healthcare providers continue to prescribe antibiotics for ARIs despite evidence that many of these infections are viral and self-limiting. The misuse of antibiotics not only contributes to increased healthcare costs but also exacerbates the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

The cluster randomized trial involved multiple rural healthcare facilities and implemented a multi-faceted stewardship program focused on education and guidelines for appropriate antibiotic utilize. Participating healthcare providers received training on the proper diagnosis and management of ARIs, alongside regular feedback on their prescribing patterns.

Key Findings of the Trial

The results from this initiative were promising. The antibiotic stewardship program led to a statistically significant reduction in the rate of antibiotic prescriptions for ARIs in the intervention group compared to the control group. Key findings included:

- Reduction in antibiotic prescriptions by approximately 30% over the trial period.

- Improved adherence to clinical guidelines among healthcare providers.

- Increased patient satisfaction due to enhanced communication and education regarding the nature of their infections.

Understanding the Context

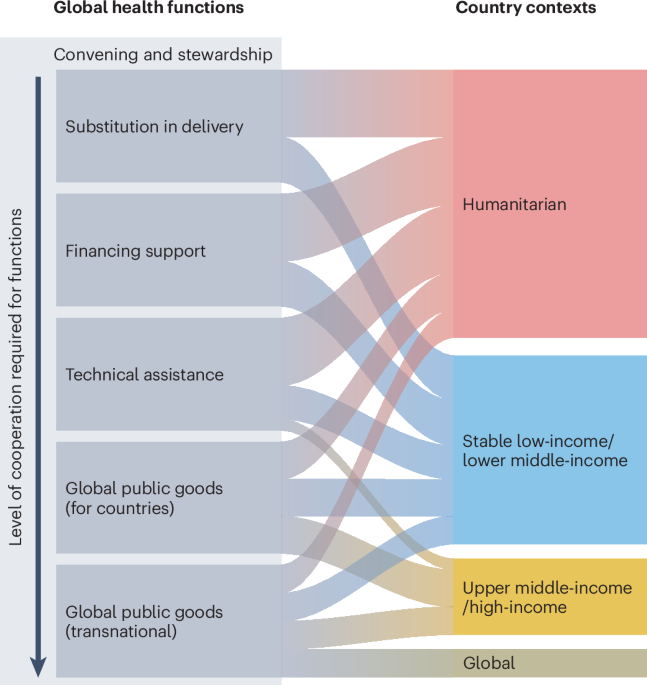

With antibiotic resistance posing a major threat to public health, especially in rural settings where access to healthcare may be limited, implementing effective stewardship programs is crucial. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that addressing antibiotic misuse is essential in combating antimicrobial resistance globally. This trial aligns with WHO’s recommendations for enhancing stewardship activities within healthcare systems.

Previous studies have shown that educational interventions can significantly influence prescribing behaviors. For example, a systematic review indicated that training and feedback mechanisms effectively decreased inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in various healthcare settings. This trial reinforces these findings, suggesting that targeted education can lead to meaningful improvements in prescribing practices.

Implications for Healthcare Providers

The successful implementation of an antibiotic stewardship program in rural healthcare facilities has several implications:

- Training and Education: Ongoing training for healthcare providers on the appropriate management of ARIs and the risks associated with unnecessary antibiotic use is crucial.

- Patient Engagement: Educating patients about the nature of their illnesses can foster better understanding and compliance, reducing demand for antibiotics.

- Policy Development: Policymakers should consider integrating similar stewardship programs into rural healthcare frameworks to enhance the quality of care.

Looking Ahead

The findings from this trial underscore the importance of addressing antibiotic prescribing practices in rural settings. As antibiotic resistance continues to rise, the need for comprehensive stewardship programs becomes even more critical. Future research should focus on sustaining these improvements and exploring the long-term impact of such interventions on public health.

As healthcare providers and policymakers operate towards implementing better practices, community engagement will play a pivotal role. Feedback from patients and continual training for providers can create a more informed healthcare environment. Readers are encouraged to share their thoughts on antibiotic use and stewardship in the comments below.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult a healthcare professional for medical concerns.