Rediscovering Tokyo’s ‘Underground‘: A Lost Era of Artistic Rebellion

Table of Contents

- 1. Rediscovering Tokyo’s ‘Underground’: A Lost Era of Artistic Rebellion

- 2. The Rise of ‘Rinding’

- 3. Echoes of a Movement: The Mori Art Museum Exhibition

- 4. A Timeline of Turmoil and Transformation

- 5. Shinjuku: The Heart of the Rebellion

- 6. The Legacy of a Lost Generation

- 7. The Enduring Relevance of Counterculture

- 8. Frequently Asked Questions About Tokyo’s Underground Movement

- 9. What role did financial constraints and engineering challenges play in delaying the realization of early subway proposals in Tokyo (1914-1930s)?

- 10. Uncovering Tokyo’s Lost Subway: Tracing the Archived history of the Underground Network Forgotten by Time

- 11. The Pre-War visions of a Tokyo Underground

- 12. The first Subway Line & Subsequent Expansion – And What Was Lost

- 13. Abandoned Station Projects & Ghost Stations

- 14. Wartime Damage & Post-War Reconstruction: A Reset for the Underground

- 15. The Rise of Private Railways & Competition

- 16. Archival Research & Documenting the Lost Network

- 17. Modern exploration & The Allure of the Forgotten

Tokyo – A recently concluded exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo has brought renewed attention to a pivotal,yet largely forgotten,period of Japanese cultural history: the “Underground” movement of the 1960s and 70s. This artistic and social upheaval, known in Japanese as rinding, challenged conventions and left an indelible mark on the nation’s creative landscape.

The Rise of ‘Rinding‘

Emerging in the wake of postwar societal shifts, the “Underground” was a response to established norms and a desire for radical expression. It mirrored similar countercultural movements unfolding globally, but quickly developed a distinctly Japanese flavor. This period saw a surge in experimental art forms, fueled by a generation eager to break free from tradition. The movement’s influence permeated various disciplines, including film, theater, music, and visual arts.

Echoes of a Movement: The Mori Art Museum Exhibition

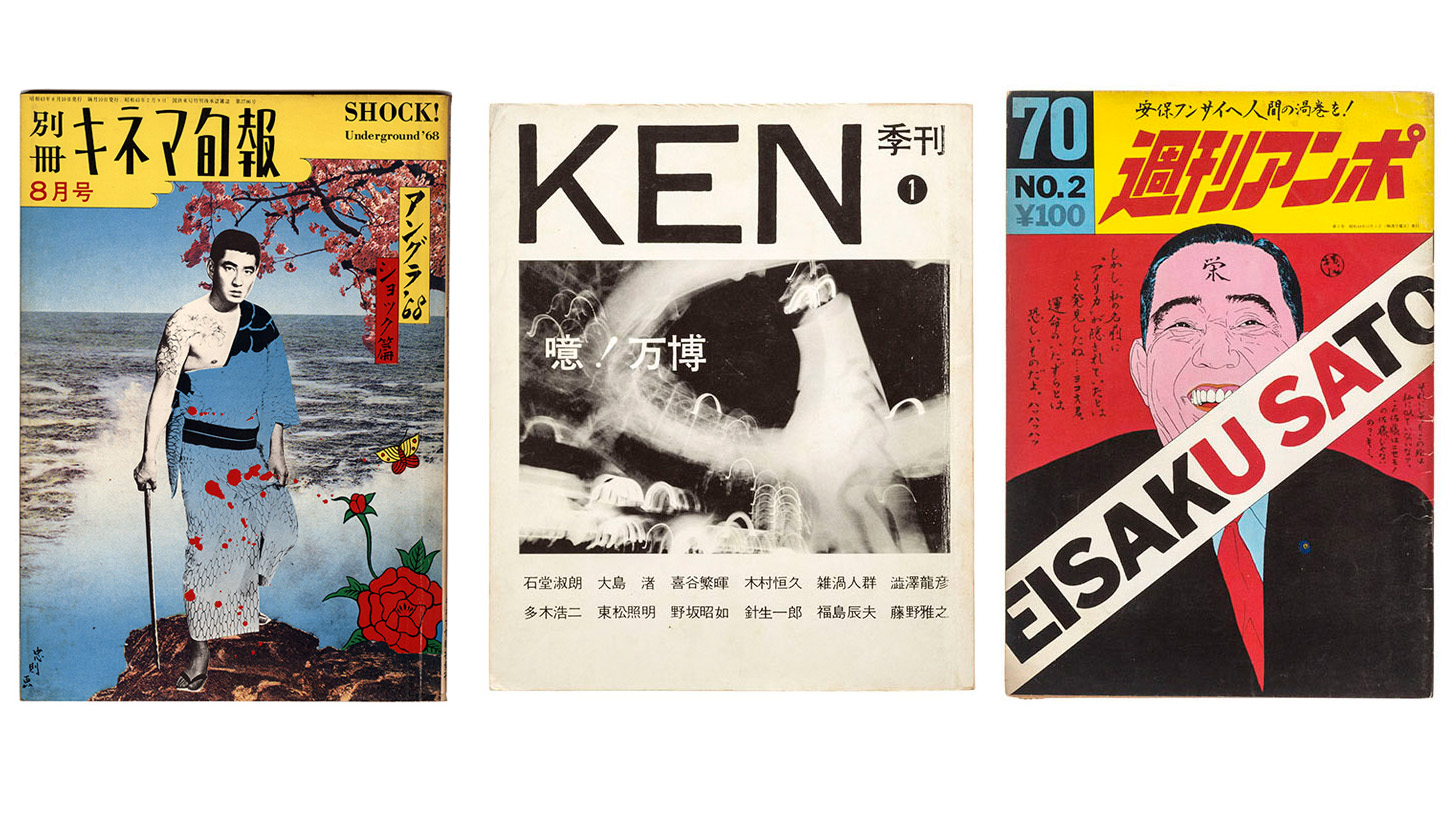

The exhibition, titled Tokyo Underground 1960-1970s: A Turning Point in Postwar Japanese culture, presented a thorough collection of ephemera from this era.Curator Kei Osawa amassed materials over two decades, including posters, flyers, magazines, and personal correspondence, offering a rare glimpse into the movement’s energy. These artifacts, frequently overlooked by customary institutions, provide invaluable insight into the spirit of the times.

A Timeline of Turmoil and Transformation

The exhibition cleverly contextualized the artistic output within the broader social and political climate of the time. Displayed alongside the artwork were chronologies detailing important events, such as the start of the Cultural Revolution in china, The Beatles’ historic Japan tour, and widespread protests against the presence of U.S. military forces. These ancient markers underscored the urgency and rebellious nature of the “Underground” scene.

| Year | Key Events | Impact on “Underground” Movement |

|---|---|---|

| 1966 | “Underground Cinema” organized by Kenji Kanesaka; Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” performance. | Catalyzed the spread of countercultural ideas; established Sogetsu Art Center as a hub. |

| 1969 | “Anti-Expo Black Festival” organized in protest. | Demonstrated opposition to political agreements and societal conventions. |

| 1970s | Waning of protest movements; shift towards economic progress. | Dissolution of the “Underground” as participants adapted or moved into mainstream culture. |

Shinjuku: The Heart of the Rebellion

The bustling district of Shinjuku served as the epicenter of this cultural ferment. Its dynamic and transient nature provided a fertile ground for gatherings and performances. the Art Theater Guild’s Scorpio Theatre became a crucial venue, hosting screenings and fostering a sense of community amongst artists and activists. the area’s energy can still be felt today, although much has changed.

Did You Know? Shinjuku Station is one of the busiest transportation hubs in the world, handling over 3.5 million passengers daily, as of 2024.

The Legacy of a Lost Generation

By the mid-1970s, the “underground” movement had largely dissipated, with many participants pursuing new paths.but its impact on Japanese art and culture remains profound. The exhibition at the Mori Art Museum served as a potent reminder of this transformative period, prompting reflection on the nature of artistic expression and social change. Considering today’s increasingly regulated digital landscape, it spurs conversations about spaces that allow for free thought and dissent.

Pro Tip: Exploring Tokyo’s subcultures can offer insights intothe country’s evolving artistic expression. Visit independent galleries and music venues for a taste of contemporary creativity.

The Enduring Relevance of Counterculture

The story of Tokyo’s “Underground” is a microcosm of global countercultural movements throughout history. These periods of rebellion often emerge in response to political, social, and economic pressures, and always leave a lasting mark on society. From the Beat Generation in the 1950s to the punk rock scene of the 1970s, challenging the status quo has always been a catalyst for artistic innovation. The lessons from these past movements can definitely help us understand the dynamics of social change in the present.

Frequently Asked Questions About Tokyo’s Underground Movement

- What was the ‘Tokyo Underground’ movement? It was a countercultural artistic movement in Japan during the 1960s and 70s that challenged societal norms and embraced experimental art forms.

- Where did the ‘Underground’ movement primarily take place? The movement largely centered in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, particularly in venues like the Scorpio Theatre.

- What types of art were prominent in the ‘Tokyo underground’? The movement encompassed a wide range of art forms, including film, theater, music, graphic design, and visual arts.

- Who was Kei Osawa and what was his role? Kei Osawa was the curator of the Tokyo Underground 1960-1970s exhibition at the Mori Art Museum and collected many of the materials showcased.

- Why is the ‘Tokyo Underground’ movement vital today? It offers insights into a crucial period of Japanese history and raises questions about artistic expression and social dissent in contemporary society.

What aspects of the “underground” movement resonate most with you, and how does it compare to contemporary expressions of rebellion in the digital age? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

What role did financial constraints and engineering challenges play in delaying the realization of early subway proposals in Tokyo (1914-1930s)?

Uncovering Tokyo’s Lost Subway: Tracing the Archived history of the Underground Network Forgotten by Time

The Pre-War visions of a Tokyo Underground

Tokyo’s current subway system is a marvel of efficiency, transporting millions daily. But beneath the sleek modernity lies a history of abandoned plans, experimental lines, and “ghost stations” – remnants of a Tokyo that never quite was. The earliest concepts for a Tokyo subway date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, heavily influenced by the burgeoning underground networks in london and Paris. These initial proposals weren’t about mass transit as we know it today; they were largely conceived to alleviate surface traffic congestion caused by the rapid growth of the city and to facilitate the movement of goods.

early Proposals (1914-1930s): Several private railway companies submitted plans, but financial constraints and engineering challenges proved insurmountable.these early designs frequently enough focused on radial lines emanating from central Tokyo.

the Influence of Foreign Systems: The London Underground and the Paris Métro served as key models, inspiring both the technical aspects and the perceived benefits of an underground railway.

Focus on freight: initial plans frequently prioritized the transport of goods, reflecting the economic needs of a rapidly industrializing Japan.

The first Subway Line & Subsequent Expansion – And What Was Lost

The first section of what would become the Tokyo Metro Ginza Line opened in 1927, a landmark achievement. However, even during this initial construction and subsequent expansions throughout the pre-war period, plans were altered and sections abandoned. The rapid pace of urban progress frequently enough outstripped the ability to finalize routes, leading to truncated lines and stations built with future extensions in mind that never materialized.

Abandoned Station Projects & Ghost Stations

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Tokyo’s lost subway history is the existence of “ghost stations” – stations constructed but never opened, or stations that were closed and sealed off.

Kasuga Station (Ginza Line): Built in the 1930s, this station was intended to serve the Imperial Household Agency. It was completed but never opened to the public due to security concerns and changes in the surrounding area. It remains largely intact, a fascinating relic of a bygone era.

shibasaki Station (Tozai Line): Another example of a station built but never used, intended to serve a planned industrial area that didn’t fully develop.

Unrealized Extensions: Numerous planned extensions to existing lines were scrapped due to wartime disruptions, post-war reconstruction priorities, and shifting demographics.these often involved stations that were partially constructed before work was halted.

Wartime Damage & Post-War Reconstruction: A Reset for the Underground

World War II inflicted significant damage on Tokyo’s infrastructure, including the fledgling subway system.Bombing raids destroyed sections of track, damaged stations, and disrupted service. The post-war reconstruction period presented an opportunity to rebuild and expand the network, but also lead to the abandonment of some pre-war plans.

Wartime Destruction: The Ginza Line suffered considerable damage, requiring extensive repairs and reconstruction.

Shifting Priorities: Post-war reconstruction focused on essential services and economic recovery, leading to a reassessment of subway expansion plans.

New Technologies & Planning: The introduction of new tunneling techniques and urban planning philosophies influenced the design and construction of the post-war subway network.

The Rise of Private Railways & Competition

The development of Tokyo’s subway system wasn’t solely the domain of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Private railway companies played a crucial role, often competing with the subway for passengers and market share. This competition sometimes led to overlapping routes and the abandonment of subway extensions in favor of private railway lines.

Tokyu, Seibu, and Keio: These major private railway companies established extensive networks that complemented and sometimes rivaled the subway system.

Route Overlap & Competition: The presence of multiple railway operators created a complex transportation landscape, with both competition and integration.

Impact on Subway Planning: The success of private railways influenced the Tokyo Metropolitan government’s subway planning decisions, leading to a more strategic approach to expansion.

Archival Research & Documenting the Lost Network

Uncovering the history of Tokyo’s lost subway requires diligent archival research. Key sources include:

Tokyo Metropolitan Government archives: Holds historical maps, construction plans, and official documents related to the subway system.

Railway Company Archives: Private railway companies maintain their own archives, containing valuable information about their involvement in tokyo’s transportation network.

Newspaper Archives: Contemporary newspaper articles provide insights into the planning, construction, and operation of the subway system.

Historical Societies & Enthusiast Groups: Local historical societies and railway enthusiast groups often possess unique collections of photographs, documents, and oral histories.

Modern exploration & The Allure of the Forgotten

Today, exploring the remnants of Tokyo’s lost subway is a niche pursuit for urban explorers and history buffs. While access to abandoned stations is generally restricted, the stories and photographs of these forgotten places continue to fascinate. The allure lies in the glimpse they offer into a different vision of Tokyo – a city that could have been.

Urban Exploration (with caution): While tempting, unauthorized access to abandoned stations is illegal and risky.

Documentary Projects: Several documentary projects have focused on