In recent years, colorectal cancer (CRC) has emerged as a significant public health concern, particularly among older adults. The SCREESCO randomized controlled trial, conducted across 18 regions in Sweden, has provided novel insights into the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening methods, specifically comparing primary colonoscopy and fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) against usual care. This large-scale trial involved approximately 278,280 participants aged 60 years and older who had not previously been screened for CRC.

The SCREESCO trial aimed to assess the impact of these screening methods on colorectal cancer mortality over a 15-year period. As the study progresses, it seeks to determine whether introducing organized screening programs, particularly in populations without prior screening access, can reduce mortality rates associated with colorectal cancer.

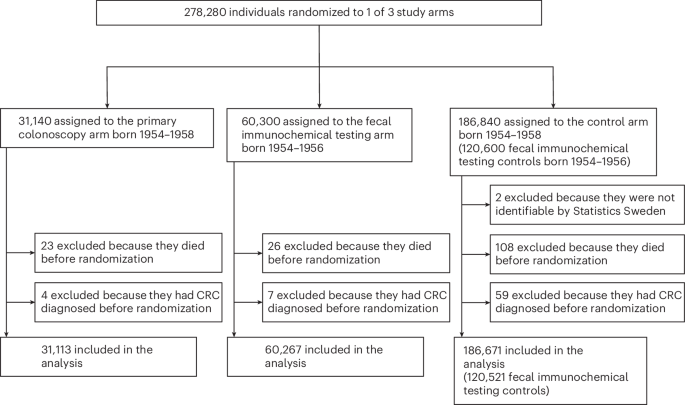

The study was meticulously designed, enrolling participants between February 2014 and May 2018. Those assigned to the intervention groups underwent either a once-only primary colonoscopy or two rounds of FIT two years apart. The control group, received no organized screening program. This approach allows researchers to compare outcomes effectively, particularly focusing on CRC incidence and mortality.

Study Methodology and Design

Participants were selected from the Total Population Register maintained by the Swedish Tax Agency. Individuals aged 60 years or those turning 60 during the study period were identified, while those with a prior CRC diagnosis or who had participated in other screening trials were excluded from the study. Following ethical approval from the Stockholm Ethics Committee, all participants provided informed consent for the screening procedures.

Randomization was conducted using a block method to ensure a fair distribution of participants across the three groups: primary colonoscopy, FIT×2, and usual care. Due to lower-than-expected participation in the primary colonoscopy arm, additional individuals were recruited, bringing the total number of randomized individuals to approximately 278,280. This adjustment aimed to ensure that the study maintained adequate statistical power to detect meaningful differences in mortality rates.

Screening Interventions and Their Implementation

Participants assigned to the primary colonoscopy group received a letter detailing the study and were encouraged to schedule their procedure. For those in the FIT×2 group, kits for two stool samples were distributed for analysis, with a fecal hemoglobin concentration of ≥10 μg/g deemed positive and prompting a colonoscopy invitation. Colonoscopies were carried out by trained endoscopists at 33 hospitals across Sweden.

Throughout the diagnostic phase, which lasted from 2014 to 2020, the study meticulously monitored CRC diagnoses, including the stage at which cancers were detected. This data was linked to various health registers to track outcomes effectively, including adverse events related to the screening processes.

Findings and Future Implications

While the primary endpoint of the SCREESCO trial focuses on CRC mortality, secondary outcomes include CRC incidence and the quality of the colonoscopies performed. The trial is designed to follow participants until December 31, 2030, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the long-term effects of screening on colorectal cancer outcomes.

Interim analyses have already indicated significant findings, particularly regarding early-stage CRC detections and the safety of the screening methods employed. Serious adverse events post-colonoscopy were tracked, contributing to a wealth of data regarding the overall safety of these procedures.

The implications of the SCREESCO trial could be substantial, potentially influencing national guidelines and policies regarding CRC screening in Sweden and beyond. As the study progresses, its results may provide critical insights into optimizing screening strategies, particularly for populations previously lacking access to organized screening programs.

With colorectal cancer being one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths globally, the findings from SCREESCO could pave the way for enhanced early detection strategies, improved patient outcomes, and reduced mortality rates from this disease.

As the study continues, it will be crucial to engage with the public and healthcare professionals to disseminate findings and encourage participation in screening programs. Increased awareness about the importance of early detection in colorectal cancer can assist in fostering a proactive approach to health and wellness.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. For personalized recommendations, please consult a healthcare professional.