Ancient Spider ancestor Rewrites Evolutionary History – And Hints at why insects Developed Wings

Table of Contents

- 1. Ancient Spider ancestor Rewrites Evolutionary History – And Hints at why insects Developed Wings

- 2. How did the deutocerebrum and tritocerebrum contribute to the survival of early spiders in their habitat?

- 3. The Dawn of Spiders: Unearthing the Ancient Brains That Shaped Arachnids

- 4. The Pre-Spider World: Ancient Arachnid Ancestors

- 5. The Rise of Silk: A Revolutionary Adaptation

- 6. The Evolution of Spinnerets

- 7. Brain Development and Sensory Systems

- 8. Key Brain Regions and their Functions

- 9. Fossil Discoveries Illuminating Spider History

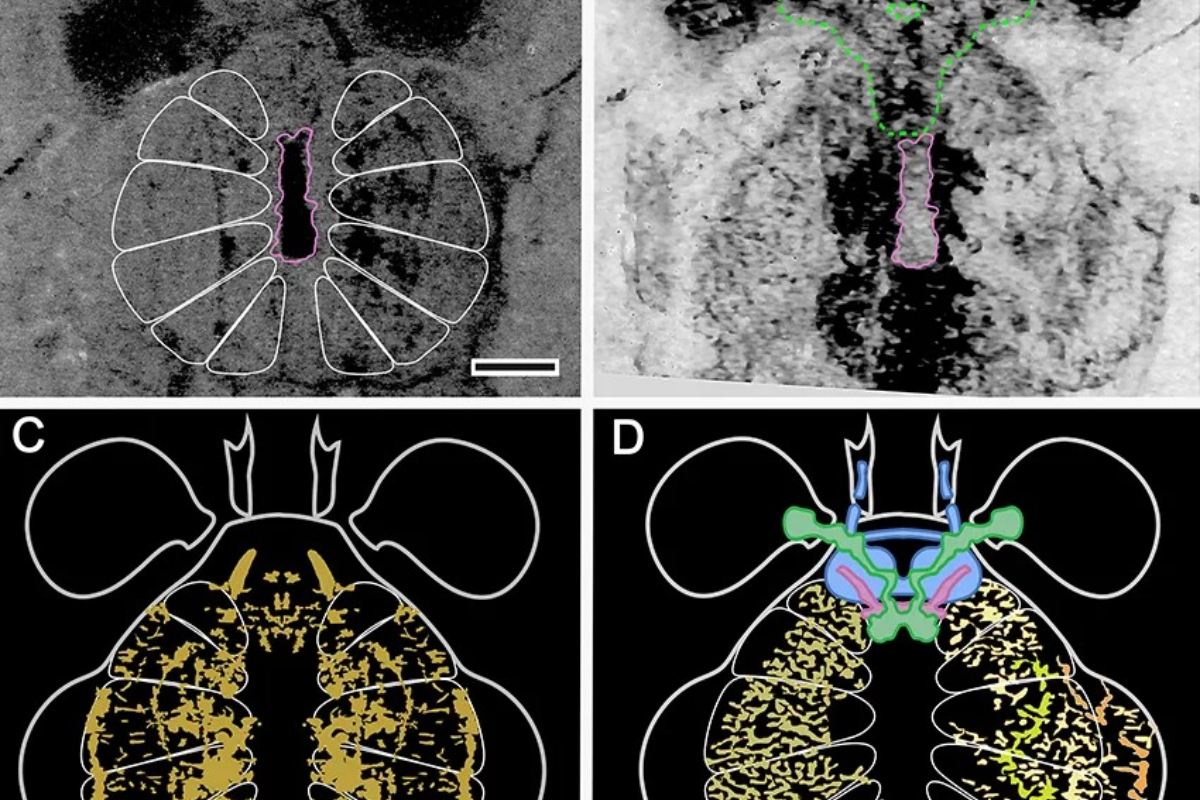

Rocky Mountains, Canada – A groundbreaking fossil finding is challenging long-held beliefs about the evolution of spiders and insects. Researchers analyzing a 515-million-year-old fossil, Mollisonia symmetrica, have found its brain structure surprisingly resembles that of modern spiders, suggesting arachnids diverged from other arthropods – including the lineage leading to insects – much earlier than previously thought.

The findings, published after a detailed study of the fossil unearthed in the Burgess Shale formation, reveal M.symmetrica possessed a brain organization distinct from horseshoe crabs and other contemporary arthropods.Rather, key features mirrored those found in today’s spiders.

“It’s as if the brain structure common to horseshoe crabs, crustaceans, and even modern insects has been ‘reversed,’ as we see in spiders,” explains Dr. Strausfeld, a lead researcher on the project. This reversal indicates a important evolutionary split occurred far back in the Cambrian period.

M. symmetrica itself was a formidable predator for its time, boasting a segmented body, a rounded carapace, and six pairs of limbs for hunting. Its existence pushes back the known origins of the arachnid lineage to around 400 million years ago.

But the implications extend beyond spider evolution. Scientists theorize that the predatory prowess of early arachnids – and specifically, their hunting speed and skill on land – may have directly driven the evolution of flight in insects.

“The ability to fly would have been a huge advantage when escaping spiders,” Dr. Strausfeld notes. “However,even wiht flight,insects remain vulnerable to the intricate silk traps woven by their arachnid predators.”

Researchers utilized elegant computer analysis, comparing brain and body features across a wide range of arthropods, both living and extinct, to confirm the kinship between M. symmetrica and modern spiders. The analysis strongly supports the idea that the Mollisonia lineage ultimately gave rise to the arachnid group, possibly birthing “the most accomplished arthropod predators in the world.”

Why This Matters: A Deeper Look at Arthropod Evolution

This discovery isn’t just about rewriting timelines. It highlights the complex and often unpredictable nature of evolution.Arthropods – insects, spiders, crustaceans, and more – represent over 80% of all known animal species. Understanding their early evolutionary relationships is crucial to understanding the biodiversity we see today.

the Cambrian explosion, a period of rapid diversification of life around 541 million years ago, remains a key area of research. Fossils like M.symmetrica provide vital clues to unraveling the mysteries of this pivotal moment in Earth’s history.

Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of brain structure as a key indicator of evolutionary divergence. The unique brain organization of M.symmetrica suggests that neurological development played a significant role in shaping the distinct evolutionary paths of arachnids and insects.

this research, originally reported by Live Science, continues to fuel debate and further inquiry into the origins of some of Earth’s most engaging creatures.The story of M. symmetrica is a powerful reminder that the fossil record holds untold secrets, waiting to be unearthed and analyzed, constantly reshaping our understanding of life’s long and intricate journey.

How did the deutocerebrum and tritocerebrum contribute to the survival of early spiders in their habitat?

The Dawn of Spiders: Unearthing the Ancient Brains That Shaped Arachnids

The Pre-Spider World: Ancient Arachnid Ancestors

Long before the intricate webs and venomous bites we associate with modern spiders, their ancestors were navigating a very different world.Understanding the evolution of spiders requires looking back over 400 million years to the silurian and Devonian periods. These early arachnids weren’t spiders as we know them, but belonged to a group called Uraraneids.Fossil evidence, primarily from Scotland, reveals these creatures were terrestrial, possessing segmented bodies and likely preying on small invertebrates.

Uraraneids: Considered the oldest known arachnid fossils,lacking true spinnerets.

Pulmonoscorpiids: Another early group, resembling scorpions but with a more flattened body plan, suggesting a different lifestyle.

Micropharyngodon: A marine creature with arachnid-like features,hinting at a possible aquatic origin for the arachnid lineage.

These early forms demonstrate that the building blocks of spider anatomy – segmented bodies, chelicerae (mouthparts), and multiple legs – were present long before the growth of silk production and elegant hunting strategies.The arachnid family tree is complex, and pinpointing the exact transition to true spiders is an ongoing area of research.

The Rise of Silk: A Revolutionary Adaptation

The development of silk was a pivotal moment in spider evolution. While not all spiders build webs, the ability to produce silk offered a multitude of advantages, from prey capture and wrapping eggs to building shelters and even ballooning (dispersing via air currents).

The Evolution of Spinnerets

The earliest silk-producing structures weren’t the complex spinnerets we see today. Initial silk production likely involved simple, tube-like structures on the abdomen. Over time, these evolved into the sophisticated spinnerets found in modern spiders, capable of producing different types of silk for various purposes.

Major Ampullate Silk: Used for draglines and the structural framework of orb webs.

Minor Ampullate Silk: Provides sticky capture threads in orb webs.

Flagelliform Silk: Highly elastic silk used in the spiral capture threads of orb webs.

Aggregate Silk: Used for egg sacs and wrapping prey.

The genetic basis for silk production is well-studied, revealing a fascinating interplay of genes controlling protein composition and spinneret morphology. spider silk genes are a subject of intense research due to the materialS remarkable strength and elasticity.

Brain Development and Sensory Systems

As spiders diversified, their brains and sensory systems underwent meaningful changes. The spider brain is relatively small, but highly centralized, controlling complex behaviors like web building, hunting, and mating.

Key Brain Regions and their Functions

Protocerebrum: Responsible for learning, memory, and visual processing.

Deutocerebrum: Processes olfactory information (smell).

Tritocerebrum: Integrates sensory information and controls motor functions.

Spiders rely heavily on sensory input to navigate their environment.

Slit Sensilla: Detect air currents and vibrations, crucial for detecting prey and predators.

Trichobothria: highly sensitive hairs that detect even the slightest changes in air movement.

Simple Eyes: Most spiders have eight eyes, arranged in various patterns, providing a wide field of vision and excellent motion detection. Though, visual acuity varies greatly between species.

Fossil Discoveries Illuminating Spider History

Paleontological discoveries continue to refine our understanding of ancient spiders. Several key fossils have provided crucial insights into spider evolution.

Attercopus: A 386-million-year-old fossil from Scotland, possessing spinneret-like structures, suggesting early silk production.

Paleozoic Spiders: Fossils from the Carboniferous period (359-299 million years ago) show more advanced spider forms, including those with web-building capabilities.

Amber Preservation: Insects and spiders preserved in amber provide exceptional detail, allowing scientists to study their anatomy and behavior.

These fossils demonstrate a gradual transition from primitive arachnids to the diverse array of spiders we see today. Spider fossils are relatively rare, making each discovery incredibly