The Censored Scripture: How the “Slave Bible” Foreshadows Modern Information Control

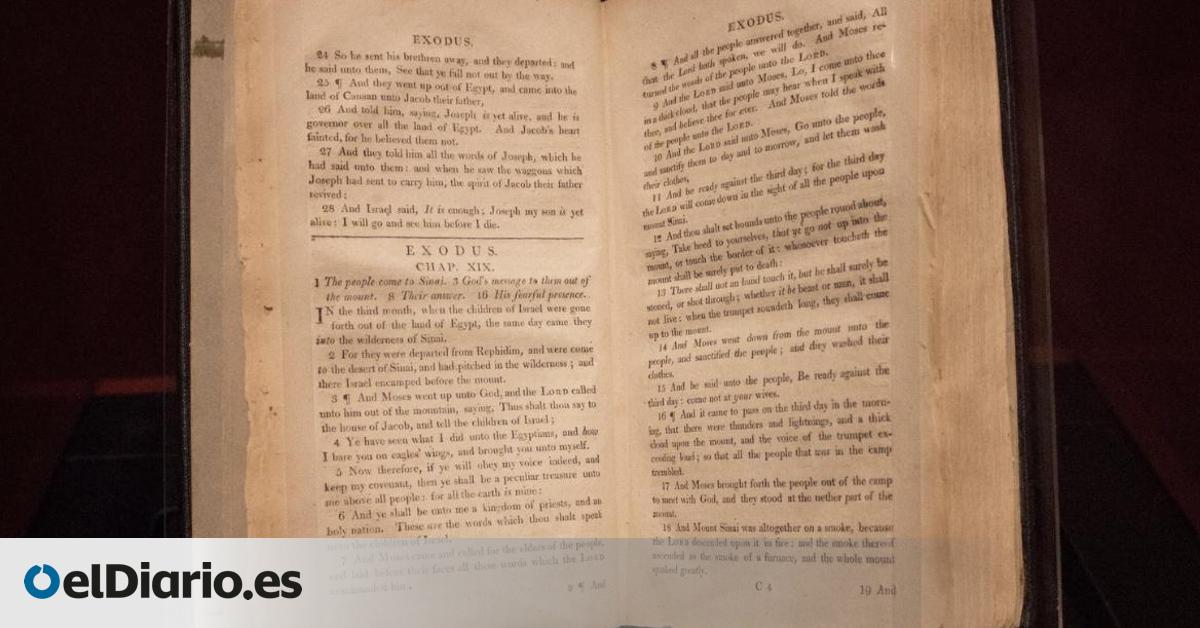

In 1807, as the British Empire began to outlaw the transatlantic slave trade, a chillingly pragmatic act of control took place. The Society for the Conversion of Black Slaves published a heavily abridged Bible, designed not to liberate, but to pacify. This “Slave Bible,” containing roughly a third of the standard Protestant text, systematically removed passages that spoke of freedom, justice, and resistance – stories like the Exodus and verses emphasizing spiritual equality. Its existence isn’t just a historical footnote; it’s a stark warning about the enduring power of curated narratives and the potential for information to be weaponized, a pattern we’re seeing echoed in increasingly sophisticated ways today.

A History of Scriptural Subjugation

The rationale behind this censorship was brutally clear. British authorities, haunted by the Haitian Revolution – the first successful slave revolt leading to an independent state – feared similar uprisings in their Caribbean colonies. As historian Anthony Schmidt, director of Collections at the Museum of the Bible, explained, editors believed stories of liberation, like that of Moses, could incite rebellion. The removal wasn’t haphazard; entire books were excised, not individual phrases. Theologian Robert Beckford of the Queen’s Foundation of Birmingham, further clarifies that the remaining passages were deliberately chosen to reinforce obedience and legitimize servitude, presenting submission as a divine virtue. Paul’s instruction to “Slaves, obey your masters” remained, while the promise of liberation was silenced.

Beyond the 19th Century: The Evolution of Narrative Control

While the “Slave Bible” represents a particularly egregious example of information manipulation, the underlying principle – controlling the narrative to maintain power – is timeless. Today, we see this manifested in far more subtle, yet pervasive, forms. The rise of algorithmic curation on social media platforms, for example, creates personalized “information bubbles” where users are primarily exposed to viewpoints that confirm their existing beliefs. This isn’t necessarily malicious intent, but the effect can be remarkably similar: a narrowing of perspective and a reinforcement of the status quo. The difference lies in the scale and sophistication. Where the Society for the Conversion of Black Slaves physically altered a sacred text, modern actors leverage data analytics and behavioral psychology to shape perceptions without overt censorship.

The Echoes of Censorship in the Digital Age

Consider the proliferation of “fake news” and disinformation campaigns. These aren’t simply about presenting false information; they’re about eroding trust in legitimate sources and creating a climate of uncertainty. The goal isn’t always to convince people of a specific falsehood, but to sow doubt and paralyze critical thinking. Similarly, the increasing use of AI-generated content raises concerns about the potential for automated propaganda and the blurring of lines between authentic and synthetic information. The ability to create convincing, yet entirely fabricated, narratives is becoming increasingly accessible, posing a significant threat to informed public discourse. This is where the lessons of the “Slave Bible” become particularly relevant. It demonstrates that controlling access to information, or manipulating its content, is a powerful tool for maintaining control.

The Anglican Church’s Role and Modern Accountability

The Anglican Church’s direct involvement in the slave trade and the publication of the “Slave Bible” is a painful chapter in its history. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Abroad, an arm of the Church, owned plantations and actively participated in the system. The recent apology from the Archbishop of Canterbury and the establishment of a £100 million (approximately $135 million) fund for reparative justice represent a crucial step towards acknowledging this past and addressing its ongoing consequences. This highlights a broader trend: a growing demand for accountability from institutions that have historically benefited from exploitation and oppression. In the digital age, this translates to calls for greater transparency from tech companies and increased regulation of social media platforms to combat the spread of misinformation and protect user privacy.

The Catholic Church’s Divergent Approach

Interestingly, the Catholic Church did not produce an equivalent censored Bible. As Jesus Folgado, a professor of Church History, points out, the texts suppressed by the Anglican Church were often those condemned by Popes as incompatible with the inherent dignity of all people. Pope Paul III, in 1537, explicitly declared that all individuals, regardless of race, deserved freedom. While acknowledging that servitude existed within Spanish and Portuguese colonies under religious orders, Folgado notes the conditions were generally less extreme than those on British plantations. This difference underscores the complex interplay of theological interpretation and political expediency, a dynamic that continues to shape debates about social justice today.

Looking Ahead: Cultivating Critical Information Literacy

Only three copies of the “Slave Bible” remain, a haunting reminder of a deliberate attempt to control minds and maintain a brutal system. Its survival serves as a testament to the enduring power of truth and the importance of resisting manipulation. However, the challenges of information control have only become more complex in the 21st century. The key to navigating this landscape lies in cultivating critical information literacy – the ability to evaluate sources, identify biases, and discern fact from fiction. This isn’t just an individual responsibility; it requires systemic changes in education, media literacy programs, and the development of ethical guidelines for AI and social media platforms. The story of the “Slave Bible” isn’t just a historical artifact; it’s a cautionary tale about the fragility of truth and the constant need to defend it.

What strategies do you believe are most effective in combating misinformation and promoting critical thinking in the digital age? Share your thoughts in the comments below!