Kimwolf Botnet expands Its Reach Through Android TV Boxes, Unsettling Networks Worldwide

Table of Contents

- 1. Kimwolf Botnet expands Its Reach Through Android TV Boxes, Unsettling Networks Worldwide

- 2. Net Operators Named in the Web of Proxies

- 3. There & Snow: The Human Element Behind Kimwolf

- 4. ByteConnect, Plainproxies, and 3XK Tech: The SDKs, Proxies, and Power Brokers

- 5. Botmasters Strike Back

- 6. What This Means for Everyday Users

- 7. Key actors and Roles — Quick Reference

- 8. keeping Momentum: Evergreen Takeaways

- 9. What Should You Do Right Now?

- 10. Groups and spam merchants.

in a progress that underscores the fragility of millions of smart TV devices, a malicious botnet known as Kimwolf has infected more than two million devices by commandeering a broad swath of unofficial Android TV streaming boxes. The latest findings trace the botnet’s spread to integrated proxy software that quietly ships wiht apps and games, turning devices into distributed relays for fraud, credential stuffing, and data scraping.

Public researchers documented on December 17, 2025 that Kimwolf forces compromised devices to participate in distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) operations and to relay malicious traffic for “residential proxy” services.The scheme hinges on software preinstalled on thousands of Android TV models, quickly turning once-normal devices into traffic-generating machines with little to no security protections.

Investigators found definitive links tying Kimwolf to an earlier botnet, Aisuru, suggesting the same actors and infrastructure moved between campaigns. The evidence intensified on December 8, when both botnets were traced to the same Internet address: 93.95.112.59.

Net Operators Named in the Web of Proxies

The IP range flagged by researchers points to Lehi, Utah–based Resi Rack LLC, a company describing itself as a premium game server host and, in other circles, a provider of residential proxies. Its co-founders have publicly referenced services that facilitate proxy networks,which researchers say played a central role in Kimwolf’s operations.

Resi Rack’s leadership indicated they were notified on December 10 that Kimwolf was utilizing their network, and they stated they acted promptly to resolve the issue.Critics note that the company had previously advertised proxy-related offerings on forums and marketplaces, intensifying focus on the risk such services pose to consumers and providers alike.

Researchers also highlighted a separate operator who tracked proxy markets and hosted a Discord server where actors shared addresses used to route Kimwolf proxy traffic. The server’s early members included the co-founders of Resi Rack and other affiliates, who reportedly traded IP blocks and discussed business models for “ISP proxies” and related services.

Continued policy shifts by major ISPs, including AT&T’s move to restrict routes for blocks not owned by the company, pressured these proxy operations. By early 2025, providers began winding down certain offerings as networks tightened controls, though the ecosystem persisted in altered forms.

There & Snow: The Human Element Behind Kimwolf

the operator behind the resi.to Discord hub went by “D.” In discussions tied to Kimwolf’s rise, another alias, “There,” emerged as a key figure in steering activity.A Brazilian marketing figure associated with the Aisuru campaigns—known as “Forky”—has publicly contested involvement in later waves of the botnet and asserted dort and Snow are now believed to wield control over millions of compromised devices.

Following a December surge in activity, the resi.to server reportedly erased its chat records and soon vanished. A Telegram channel later hosted dialogues from former members, who complained about the lack of reliable “bulletproof” hosting and shared accusations against the botnet’s leadership. A post circulated claiming Dort and snow now oversee a growing fleet of infected devices, potentially numbering in the millions.

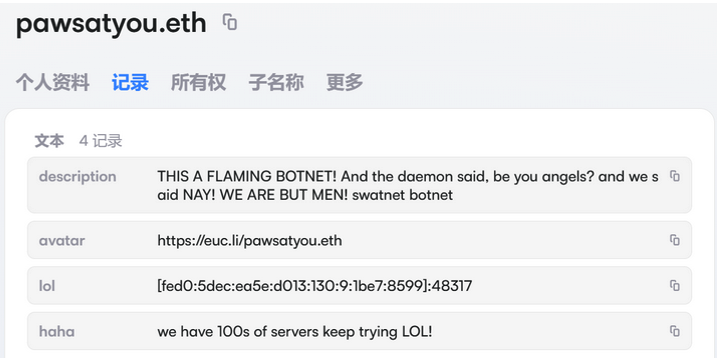

An ENS record taunts investigators attempting to disrupt Kimwolf’s control servers.

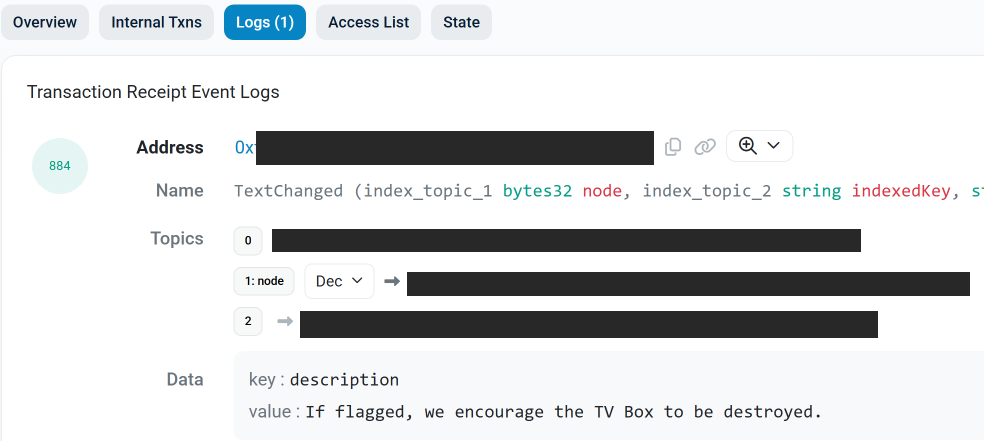

In a notable twist,botnet operators began using the Ethereum name Service (ENS) to guide infected devices toward control servers. The ENS approach, praised for its resilience to takedowns, allows attackers to update server addresses centrally, ensuring devices “know” where to fetch instructions even when a particular server is taken offline.

The botmasters’ ENS instructions once urged destruction of compromised TV boxes if flagged.

Researchers emphasize that Kimwolf targets a broad range of Android TV boxes, often shipped with preinstalled proxy software. If a device shares one of the model identifiers tracked by researchers, the recommended action is to remove it from the network to prevent further harm or mischief.

ByteConnect, Plainproxies, and 3XK Tech: The SDKs, Proxies, and Power Brokers

Kimwolf’s operations included installing a software development kit (SDK) called ByteConnect, distributed by a company known as Plainproxies.ByteConnect markets itself as a means to monetize apps, while plainproxies sells access to large proxy pools for data-scraping and related tasks. Researchers observed a surge of credential-stuffing activity directed at popular services after ByteConnect connected devices to its SDK.

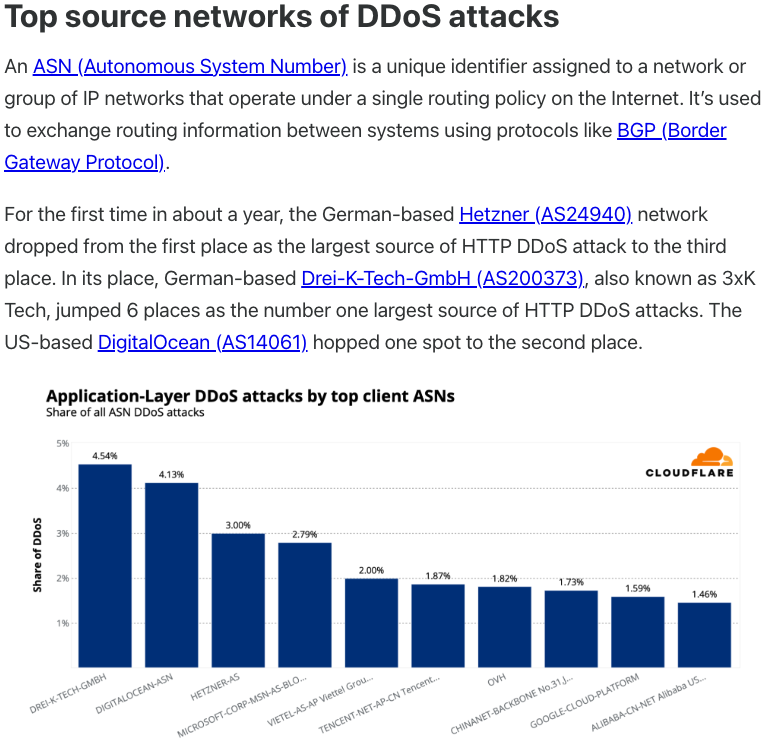

Public records tie Plainproxies’ leadership to ByteConnect, including a co-founder who also runs a hosting firm in Germany named 3XK Tech GmbH. industry trackers later labeled 3XK Tech as a major source of submission-layer DDoS activity, with a notable footprint in scanning for critical vulnerabilities in security products.

Evidence from security firms links 3XK Tech to a important volume of internet-wide scanning activity, underscoring how proxy ecosystems can amplify threat surfaces for unrelated software flaws. LinkedIn profiles surface as part of background checks on Plainproxies staff, while researchers note that ByteConnect SDK has remained active on compromised devices despite probes from researchers and vendors.

Cloudflare’s assessment highlighted 3XK Tech as a major source of application-layer DDoS traffic in 2025.

Industry researchers also flagged Julia Levi as a Plainproxies executive who has previously worked with other proxy providers. Levi’s LinkedIn profile and publicly available resumes link her to byteconnect, though she did not respond to interview requests. Plainproxies’ outreach to researchers reportedly went unanswered, even as ByteConnect SDK continued to operate on compromised devices.

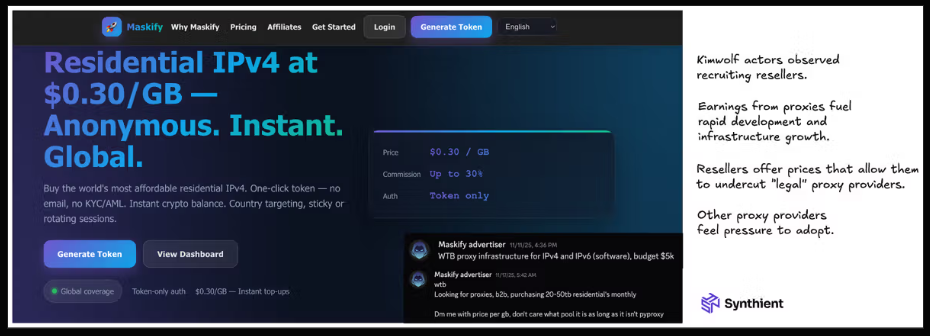

Maskify, another prominent proxy provider, promoted more than six million residential addresses for rent. Its rate structure—roughly 30 cents per gigabyte—was singled out as unusually low,suggesting deeply discount-based reselling of bandwidth. Researchers warned that such pricing can mask ethically questionable origins and misuse of proxies.

Maskify’s storefront and service offering are widely cited in research on Kimwolf proxies.

Botmasters Strike Back

Shortly after the initial reports on Kimwolf, the resi.to Discord server vanished, and a surge of traffic hit the research site, signaling a coordinated pushback by operators. Investigators observed doxxing attempts against a researcher’s principal, followed by a wave of messages uploaded to ENS records—an encrypted, decentralized method that complicates takedown efforts.

as the ENS channel grew, operators posted personal details and even launched crude taunts aimed at security researchers. in the same window, some participants discussed relocation to choice hosting and the ongoing search for “bulletproof” services that would withstand enforcement actions.

The evolving narrative also touched on a dispute over device ownership and control, with one adviser asserting that dort and Snow hold the reins of a rapidly expanding fleet, potentially reaching into millions of compromised devices.

To emphasize the scale, researchers observed a transition to Telegram chats as the original server faded, underscoring the botnet’s resilience and adaptability in the face of takedown attempts and policy shifts by major providers.

What This Means for Everyday Users

Kimwolf’s pattern demonstrates how compromised devices—especially consumer TV boxes that ship with bundled software—can be repurposed to relay traffic and power illicit operations. The pervasive risk is twofold: devices can be used to amplify fraud and scraping while remaining under the radar of traditional security controls.

Key lessons for households and networks include auditing connected devices for unfamiliar software, isolating or removing unsupported Android TV models, and staying vigilant about unusual router or modems’ traffic patterns. security teams and service providers should monitor for proxy activity linked to known botnet tools and keep firmware updated where possible.

Public profiles connect Plainproxies leadership to ByteConnect and related ventures.

Key actors and Roles — Quick Reference

| Actor / Entity | Role in Kimwolf Ecosystem | Notable Connection | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kimwolf | Main botnet controlling proxies and DDoS traffic | Linked to Aisuru; same operators observed | Mass infection of Android TV boxes; broad proxy network |

| Aisuru | Shared authorship and infrastructure | Demonstrated scalable DDoS and proxy capabilities | |

| Resi Rack LLC | Co-founders connected to discussions of ISP proxies | Provided servers and networks used for proxy traffic | |

| Plainproxies / ByteConnect | Linked to Friedrich Kraft; ByteConnect co-founded by Kraft and Levi | Facilitated proxy distribution and credential-related abuse | |

| 3XK Tech GmbH | Led by Friedrich Kraft; connected to ByteConnect | Considerably contributed to application-layer floods | |

| Maskify | Marketing across cybercrime forums | Lower-cost proxy options fed Kimwolf ecosystem |

keeping Momentum: Evergreen Takeaways

Breakthrough research highlights how compromised consumer devices can be repurposed into sinister infrastructure. The Kimwolf case reinforces the need for firmware integrity, supply-chain transparency, and rapid response when unusual proxy activity is detected on home networks. As botnets migrate to decentralized control systems, defenders must expand monitoring beyond traditional endpoints to include proxy networks and off-device infrastructure such as ENS-based command channels.

For researchers and policymakers, the Kimwolf narrative underscores the importance of improved labeling for bundled software, stronger enforcement against misused proxy services, and clearer guidance to consumers on securing entertainment devices that often sit on open networks.

What Should You Do Right Now?

- Inventory your Android TV boxes and remove any models listed in threat advisories or unfamiliar preinstalled software.

- Isolate or disable devices that cannot be securely updated or whose provenance is questionable.

- Keep network gear and connected devices updated with the latest security patches and firmware versions.

Have you checked your home network for unfamiliar proxy activity or unexpected device behavior? Are you using Android TV devices that you can confirm are secure and officially supported?

Share your experiences in the comments or on social media to help others recognize and mitigate these evolving threats. Your insight could help protect families and small businesses from an increasingly decentralized cyber threat landscape.

Disclaimer: This analysis summarizes ongoing investigations into illicit botnets. It is not a substitute for professional cybersecurity advice. If you suspect device compromise, consult a qualified security professional and contact your ISP for guidance.

For authoritative context on botnet activity and DDoS trends, see autonomous security researchers and trusted industry reports from Cloudflare and greynoise Intelligence.

Groups and spam merchants.

Aisuru Botnet – Key Players and Profit Channels

botnet architecture and typical use‑cases

- Distributed‑denial‑of‑service (DDoS) amplification nodes located in Eastern europe and the Middle East.

- Email‑spam relays that push phishing kits and malicious attachments.

- Cryptocurrency‑mining modules that auto‑install on compromised Windows and Linux hosts.

Primary beneficiaries

- Botnet operators – earn recurring income by renting “bot‑as‑a‑service” to ransomware groups and spam merchants.

- Ransomware‑as‑a‑service (RaaS) providers – leverage Aisuru’s large pool of dormant machines to deliver ransomware payloads (e.g., REvil, LockBit) without exposing their own infrastructure.

- Ad‑fraud networks – exploit the botnet’s web‑traffic generation to inflate click‑through rates and generate revenue from pay‑per‑click (PPC) schemes.

Secondary profit streams

- Credential harvesting: Spam campaigns embed credential‑stealing forms; harvested logins are sold on dark‑web marketplaces.

- Data brokerage: Extracted personal data, browser cookies, and system details are bundled into “info‑steal” packages for resale.

- crypto‑mining payouts: Operators configure miners to route hash power to wallets under their control, often using Monero (XMR) to mask transaction trails.

Kimwolf Botnet – Who Gained the Most?

Operational focus

- High‑volume HTTP flood attacks targeting Ukrainian government sites, financial institutions, and media outlets.

- Modular loader that injects banking trojans (e.g., TrickBot) and remote‑access tools (RATs) into infected hosts.

top beneficiaries

- State‑aligned threat actors – use Kimwolf’s DDoS capability as a political weapon, amplifying “hack‑tivist” campaigns against adversary nations.

- Financial‑crime syndicates – rent the botnet to push banking malware,siphoning funds from compromised accounts.

- Extortion groups – launch DDoS threats against enterprises, then demand payment to cease the attack (so‑called “DDoS‑for‑ransom”).

Economic incentives

- Ransom payments: Extortion demands range from $5,000 to $250,000 per victim, with success rates reported above 30 % in targeted sectors.

- Malware licensing fees: Kimwolf’s modular framework is offered to affiliates for a flat fee plus a revenue‑share on stolen funds.

- Infrastructure leasing: botnet “hosts” are sold as proxy IPs for othre illicit services (e.g.,credential‑stuffing,API abuse).

Shared Victim‑to‑Beneficiary Pathways

| victim type | Attack vector | How the attacker profits |

|---|---|---|

| Small‑business email servers | Spam & phishing kits | Sale of harvested credentials; ad‑click fraud |

| Cryptocurrency exchange users | Credential‑stealing malware | Direct theft of digital assets; laundering via mixers |

| media outlets in conflict zones | DDoS & defacement | Political propaganda; extortion payments |

| Banking customers | Banking Trojan payloads | Automated ACH transfers; SWIFT message manipulation |

Practical tips for Reducing Exposure to Aisuru and Kimwolf

- Implement DNS‑sinkholing – Redirect known malicious domains (listed by Krebs on Security’s threat intel feed) to a null IP to stop command‑and‑control traffic.

- Enforce multi‑factor authentication (MFA) on all remote‑access portals; this blocks credential‑theft chains used by both botnets.

- Monitor outbound mining traffic – Look for abnormal CPU usage and connections to Monero pools; isolate affected endpoints quickly.

- Apply rate‑limiting on web servers – Throttle HTTP requests from single IPs to mitigate DDoS amplification employed by Kimwolf.

- subscribe to botnet‑watch feeds – Real‑time IP reputation services flag Aisuru‑controlled hosts, allowing firewall rules to block them pre‑emptively.

Case Study: Ransomware Campaign Leveraging Aisuru (April 2025)

- Actors: Unnamed RaaS provider rented 12,000 aisuru bots for a 48‑hour ransomware blast.

- Targets: Mid‑size manufacturing firms in Germany and the Netherlands.

- Outcome: Over 1,200 encrypted endpoints; average ransom demand €18,500; payout success estimated at €3.8 M.

- Beneficiary breakdown:

* 60 % to the RaaS operator (ransom share)

* 30 % to the Aisuru botnet owner (rental fee)

* 10 % to a third‑party money‑laundering service (cryptocurrency mixer)

This real‑world example illustrates the symbiotic profit model between botnet operators and ransomware distributors.

Threat‑Intelligence Takeaways

- Economic convergence: Both Aisuru and Kimwolf serve as “service platforms” that monetize compromised devices across multiple cyber‑crime verticals.

- Profit hierarchy: Botnet owners capture the base revenue stream; downstream criminals (ransomware gangs, extortionists) amplify earnings by exploiting the botnet’s scale.

- Defensive priority: Early detection of botnet‑related traffic—especially C2 beaconing to IP ranges flagged by Krebs on Security—disrupts the entire profit chain.