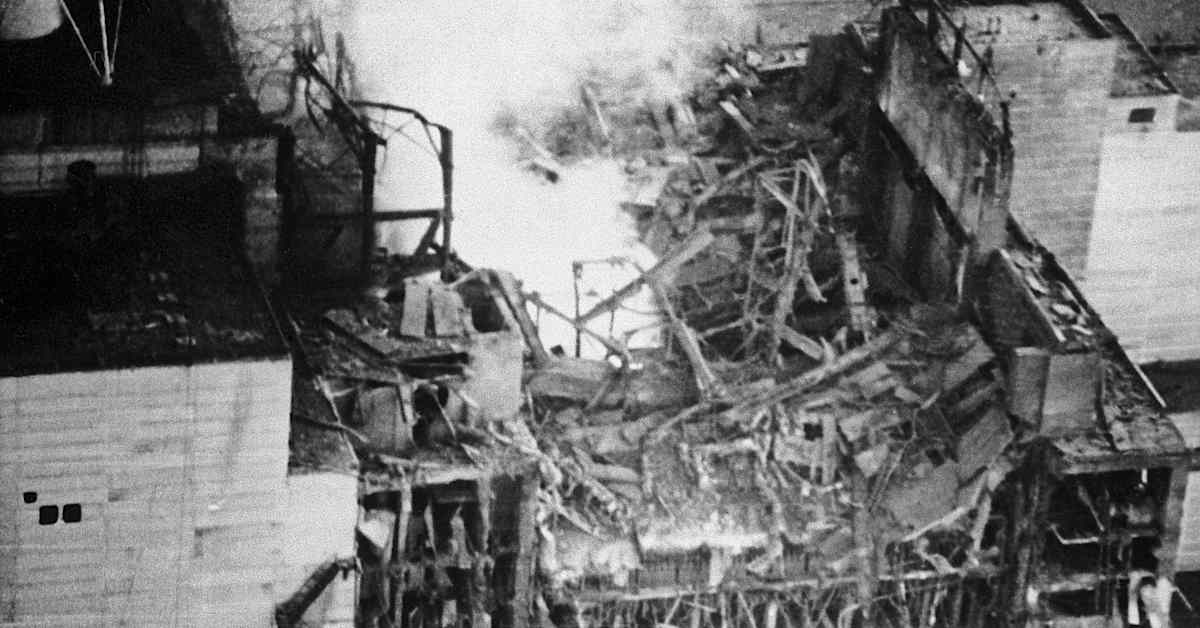

The Long Shadow of Chernobyl: How Radiation Exposure Still Impacts Academic Success Decades Later

Nearly 38 years after the Chernobyl disaster, a chilling revelation is emerging: the fallout wasn’t just a short-term health crisis. New research, building on earlier Swedish studies, demonstrates a statistically significant link between prenatal radiation exposure and diminished academic performance – a subtle but persistent impact on the life trajectories of those born in the wake of the 1986 nuclear accident. This isn’t about immediate illness; it’s about a hidden cost to cognitive development, and it raises profound questions about the long-term consequences of environmental disasters.

The Finnish Findings: A Dose-Response Relationship

The Meteorological Institute in Finland first detected elevated radiation levels on April 27, 1986, a day before the Chernobyl explosion became public knowledge. While Finland experienced relatively low levels of fallout compared to Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, recent economic research led by Matti Sipiläinen at the Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority reveals a measurable effect. The study, published in the Finnish Journal of the Finnish Economic Association, found that students exposed to higher levels of radiation in utero – specifically during pregnancy weeks 8-25 – consistently scored lower on their matriculation exams (the Finnish equivalent of A-levels) and were less likely to gain admission to university.

This isn’t a vague correlation. Sipiläinen’s research establishes a clear dose-response relationship: the higher the radiation exposure, the lower the academic results. On average, students with the highest exposure had an 8% lower score on high school essays, and a 13% lower probability of achieving a top grade (M, E, or L) in mathematics. The impact was most pronounced in subjects requiring complex reasoning, like mathematics and mother tongue, suggesting a disruption in cognitive functions.

How Radiation Interferes with Brain Development

The mechanism behind this effect is rooted in the fundamental biology of brain development. As Sipiläinen explains, radiation breaks chemical bonds, including those within DNA. During the critical period of fetal development (weeks 8-25), the brain undergoes rapid cell division. Interference with this process can have lasting consequences, as neuron regeneration is slow and limited. The study highlights the vulnerability of the developing brain to environmental toxins, even at relatively low doses.

Crucially, the research points to rainfall as a key factor in determining the extent of exposure. The initial radioactive cloud passed at a high altitude, posing minimal risk. However, when precipitation occurred, radioactive particles were brought to the ground, exposing pregnant women and their developing fetuses. Cesium-137, a long-lived isotope, served as a reliable marker for identifying areas with higher fallout concentrations, as measured by researchers from the Radiation Protection Agency who meticulously sampled surfaces across Finland.

Beyond Finland: Echoes of the Swedish Study

The Finnish findings aren’t isolated. They replicate the results of a similar study conducted in Sweden by Marten Palmen and colleagues, published in the prestigious Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE). The consistency between these independent studies, using different datasets and methodologies, significantly strengthens the evidence for a causal link between prenatal radiation exposure and cognitive outcomes. As Janne Tukiainen, editor of Sipiläinen’s research, emphasizes, the convergence of these findings makes a statistical coincidence highly improbable.

Implications for Future Disaster Preparedness and Environmental Health

The Chernobyl legacy extends far beyond the immediate devastation and the well-documented increase in thyroid cancer rates in affected regions. This research underscores the importance of considering the subtle, long-term impacts of environmental disasters on cognitive development and future opportunities. It also highlights the need for robust monitoring and accurate data collection in the aftermath of such events.

Looking ahead, several trends are becoming apparent. Firstly, the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, potentially exacerbated by climate change, could lead to the release of other environmental toxins. Secondly, advancements in neuroimaging and data analytics will allow for more precise assessment of the neurological effects of environmental exposures. Finally, a growing awareness of the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) is driving research into the long-term consequences of early-life exposures.

The Rise of Environmental Neurotoxicology

We are entering an era of environmental neurotoxicology, where the impact of pollutants on brain development and function is a central focus. This field will require interdisciplinary collaboration between toxicologists, neuroscientists, epidemiologists, and economists to fully understand the complex interplay between environmental factors and cognitive outcomes. Understanding these links is crucial for developing effective preventative measures and mitigating the long-term consequences of environmental disasters.

The lessons from Chernobyl, and now reinforced by this Finnish research, are clear: the true cost of a nuclear accident – or any large-scale environmental contamination – extends far beyond immediate casualties and visible damage. It’s a cost that can ripple through generations, subtly shaping the intellectual potential of entire populations. What further hidden impacts of past and present environmental hazards await discovery?

Explore more insights on radiation and health from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Share your thoughts in the comments below – what steps can we take to better protect future generations from the long-term effects of environmental hazards?