NASA Astronaut Nichole Ayers managed to capture an unusual image from the International Space Station (EEI): a phenomenon known as “Gigantic jet”registered on July 5 and classified by the agency as an unusual form of TLE (transient light event).

Read too

As explained by NASA in an official statement, this type of electric shock represents one of the more powerful manifestations of atmospheric activityextending from the top of a storm to the upper atmosphere.

These downloads are not easy to observe, since they are presented sporadically and are usually seen by chancemany times from aircraft or by land on land that capture other forms of electrical activity by accident. The record made from space offers an unpublished perspective of this phenomenon, rarely documented so clearly.

The giant jet spread from a storm to 100 km of altitude in the atmosphere. Photo:Nasa

Read too

An electric bridge between the clouds and the edge of space

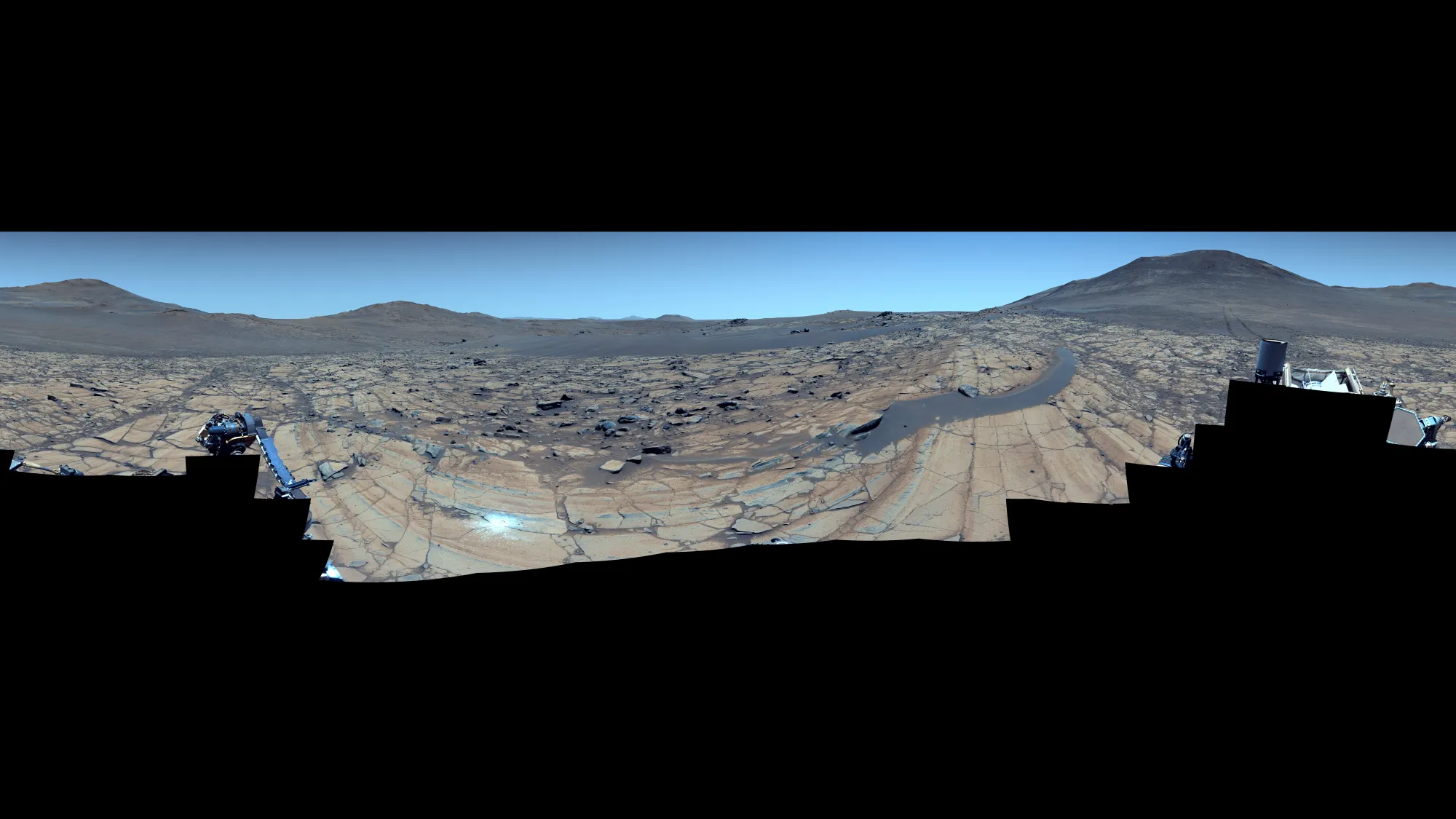

Gigantic jets occur when turbulent conditions occur in the tops of the storms, allowing rays to escape vertically from the cloud system and spread to the highest layers of the atmosphere. In this process, an electrical connection is formed between the upper part of the clouds (located approximately 20 kilometers from altitude) and the upper atmosphere, located around 100 kilometers.

Said vertical discharge deposits a considerable amount of electric charge, becoming a kind of electricity column that crosses several layers of the Earth’s atmosphere. Its study contributes to the understanding of how electricity behaves in areas where the atmosphere is thinner and physical conditions change drastically compared to the regions closest to the surface.

The NASA explained that the event was due to turbulence that allowed the ray escape. Photo:iStockphoto

Initially, The image captured by Ayers was identified as a spriteanother more commonly observed tle form. The sprites, also known as “elves”, are brief luminous flashes of reddish colors that appear high, in the mesosphere, around the 80 kilometers on the earth.

Unlike gigantic jets, sprites do not arise directly from the storm, but are generated independently to a higher altitude, as a result of extremely powerful rays that occur under. Its shape can vary: they adopt structures similar to jellyfish, columns or carrots, and can cover areas of tens of kilometers in diameter.

Read too

Sprites may appear alongside other high -atmosphere electrical phenomena, also known as TLE. Among them are the halos and the elveacronyms of light emissions and very low frequency disturbances due to electromagnetic pulses sources. These events are part of a broader set of electrical manifestations that, although they are beyond the reach of the common human vision, represent a complex and active dynamic in the high layers of the Earth’s atmosphere.

According to NASA, direct observation from the space of a gigantic stream allows us to advance in the understanding of these electrical structures that link meteorological phenomena with processes that occur on the border with space.

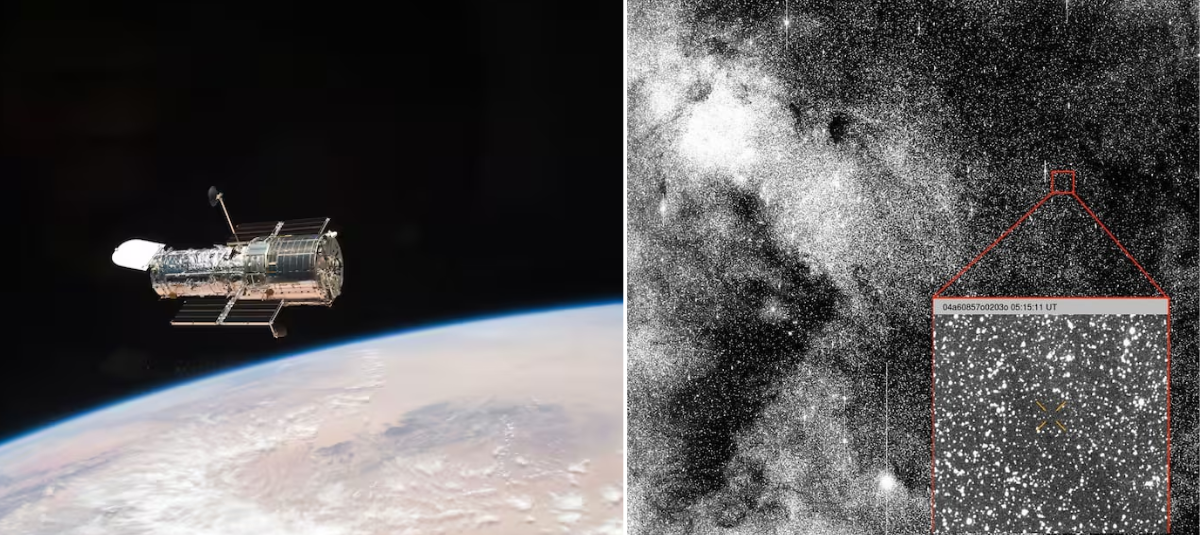

Hubble telescope photographed strange object that travels through space at a record speed

The Hubble space telescope managed to capture one of the most detailed images of an object from another star system: comet 3i/Atlas. This light blue body represents andl third interstellar object identified to date, and his behavior has caught the attention of the scientific community due to the record speed with which he moves through space.

Read too

The discovery of the kite occurred on July 1, 2025, when it was detected by the Telescope of the early alert network, located in Río Hurtado, Chile. This network, financed by NASA, is designed to locate comets and asteroids close to Earth. Subsequently, records of observatories such as El Palomar were analyzed in California, which had captured images of the kite since June 14, 2025. The object was called “3i/Atlas”, where the “I” indicates its interstellar origin.

The Hubble telescope photographed the comet on July 21, 2025, when it was 365 million kilometers from the earth and 446 million kilometers from the sun.

Europa Press

More news in time

*This content was rewritten with the assistance of an artificial intelligence, based on the information published by Europa Press, and had the review of the journalist and an editor.