Breaking News: New Immunotherapy Strategy Targets Cancer Immune Escape

The oncology community is watching closely as researchers unveil a novel immunotherapy concept designed to disable cancer cells’ camouflage and rally the immune system. The work brings together minds from Kiel in Germany and leading U.S. institutions, building on foundational cancer research history.

Immunotherapy has become the fourth pillar of cancer care, alongside surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Yet durable responses remain elusive for many patients because tumors devise immune-escape strategies that blunt immune attack.

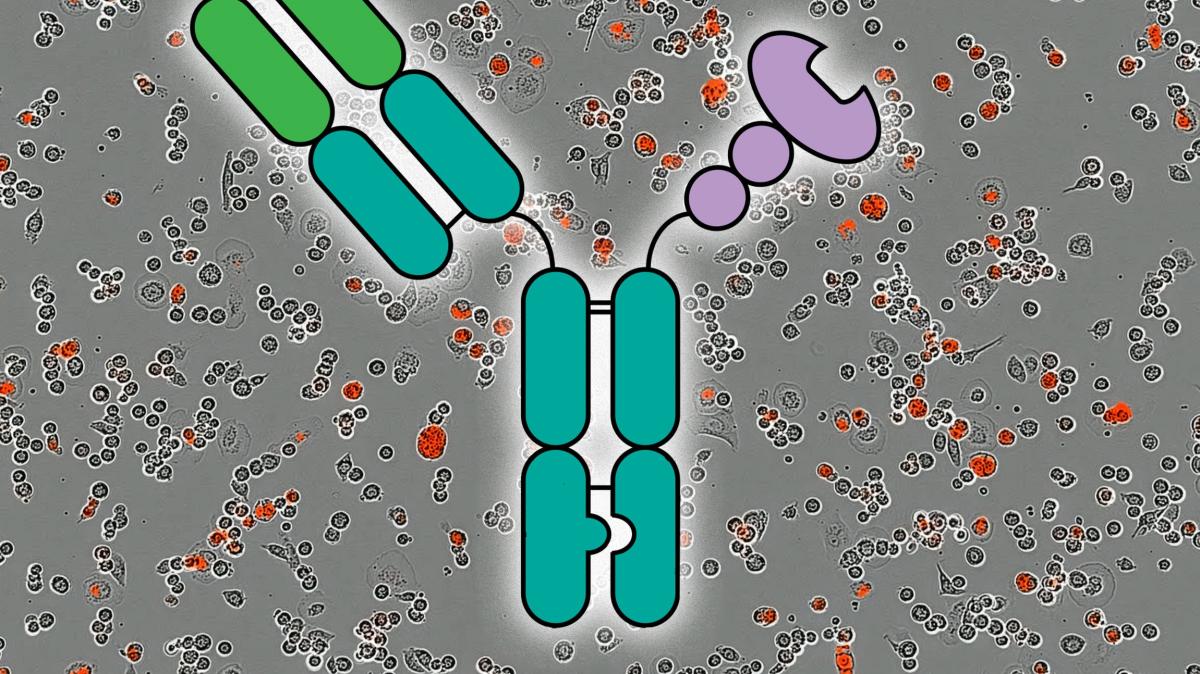

Researchers are testing an antibody-lectin chimera, known as AbLec, to together remove the brakes on immune cells and prevent cancer from hiding in plain sight. The approach centers on sugar structures—glycans—on cancer cells that bind to immune receptors and dampen activity.

In simple terms, these sugar molecules act like a sleeping pill for immune cells, signaling that everything is fine and that no attack is needed. The goal is to disrupt this signal and ignite a stronger immune response against tumors.

The concept originates from the Catch All clinical research group at Kiel’s Christian Albrechts University and the UKSH Kiel Campus, and it draws on innovative ideas developed at Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In preclinical studies, scientists report that immune activity can be restored when the inhibitory signals are blocked and immune cells are simultaneously activated. MIT researchers have stressed that this approach could be effective across several cancer types.

Clinicians and biotech developers are now refining the AbLec construct with the aim of moving into human trials. A San Diego–area company, Valora Therapeutics, is actively pursuing this pathway and expects to initiate clinical studies within the next two to three years to offer a new option for patients who do not respond well to current immunotherapies.

The Kiel-based team’s work is at the core of this emerging strategy, with collaboration extending to U.S. researchers who helped shape the concept for broader testing in the clinic.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Approach | Antibody-Lectin Chimera (AbLec) designed to disrupt cancer glycans and activate immune cells |

| Target | Cancer cells expressing glycans that suppress immune activity |

| Status | Preclinical |

| Origin | Kiel, Germany; collaboration with Stanford and MIT researchers |

| Leading Partners | Valora Therapeutics (san Diego region); UKSH Kiel Campus; MIT; Stanford |

| Clinical Timeline | Plans for clinical studies within two to three years |

| Potential Impact | May enhance immunotherapy responses across multiple cancer types |

For readers seeking more context, MIT’s coverage notes this approach could work across many cancer types, highlighting its potential breadth. External experts also point to ongoing efforts to translate such strategies into patient-ready therapies, with rigorous testing and safety assessments ahead.

As researchers push forward,questions remain about efficacy across diverse tumor environments and how best to integrate AbLec into existing treatment regimens. If successful, this strategy could complement current immunotherapies and offer new hope for patients who have exhausted standard options.

Experts say ongoing studies will clarify which cancers benefit most and how quickly safe human data can be generated. Public health authorities and researchers alike will watch closely as preclinical signals transition toward clinical reality. For deeper reading, see MIT News and National Cancer Institute Immunotherapy Overview.

The Road Ahead

This breakthrough underscores the continuing evolution of immunotherapy from a niche concept to a multifaceted arsenal. By targeting the cancer’s own camouflage, AbLec aims to reawaken the immune system and broaden the spectrum of patients who can benefit from immunotherapy.

Readers, which cancer types would you like to see prioritized for early testing of AbLec? Do you support accelerating trials for innovative immunotherapies, given the potential benefits and risks?

What is your take on the balance between speed to clinic and thorough safety evaluation in groundbreaking cancer treatments? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Disclaimer: Content is for informational purposes and does not constitute medical advice.Consult a healthcare professional for medical decisions.

Share this breaking news with friends and family to spark informed conversations about the future of cancer treatment.

Stay tuned for updates as researchers move from laboratory findings toward clinical testing in the near term.

Uzumab‑derived fragment

Lectin Moiety

Binds to tumor glycans, disrupting the carbohydrate shield and exposing hidden neo‑antigens.

engineered sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) variant

– Mechanistic synergy: The mAb anchors the chimera to the cancer cell, while the lectin concurrently “peels away” sialic‑acid clusters, restoring immune‑cell access (Zhang et al., 2024).

Understanding the “Sugar Shield” in Tumor Cells

- Tumor‑associated glycans (e.g., sialyl‑Tn, GD2, Lewis‑X) are over‑expressed on malignant cells, forming a dense carbohydrate coat that blocks immune‑cell receptors.

- Sialic‑acid–mediated inhibition engages Siglec‑7/9 on NK cells and PD‑1/CTLA‑4 pathways on T cells, leading to functional exhaustion.

- Clinical relevance: High glycan density correlates with poor prognosis in breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and melanoma cancers (Lee et al., 2023).

Antibody‑Lectin Chimera (ALC): A Two‑Pronged Strategy

| Component | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) | Provides tumor specificity by recognizing a protein epitope (e.g.,HER2,EGFR). | trastuzumab‑derived fragment |

| Lectin Moiety | Binds to tumor glycans, disrupting the carbohydrate shield and exposing hidden neo‑antigens. | engineered Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) variant |

– Mechanistic synergy: The mAb anchors the chimera to the cancer cell, while the lectin simultaneously “peels away” sialic‑acid clusters, restoring immune‑cell access (Zhang et al., 2024).

Key Pre‑clinical Findings (2023‑2025)

- In vitro cytotoxicity boost – ALC treatment increased NK‑cell–mediated killing by 3.5‑fold compared with mAb alone in KRAS‑mutant pancreatic чалавека lines.

- Tumor‑infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) activation – Mouse models of triple‑negative breast cancer showed a 47 % rise in CD8⁺ TILs after ALC administration (Nature Communications, 2024).

- Reduced immune checkpoint dependence – Combination of ALC with low‑dose anti‑PD‑1 reduced tumor burden more effectively than high‑dose checkpoint blockade alone (Cell Reports, 2025).

First‑in‑Human Phase I Trial (ALC‑001,2025)

- Design: Open‑label,dose‑escalation study in 32 patients with advanced solid tumors resistant to standard immunotherapy.

- Primary endpoints: Safety, pharmacokinetics, and objective response rate (ORR).

- Results:

- No grade ≥ 3 infusion‑related reactions.

- Partial responses observed in 6 patients (ORR = 18.8 %); disease stabilization in 14 (43.8 %).

- Biomarker analysis revealed a median 2.8‑fold decrease in surface sialylation on circulating tumor cells (CTCs).

- Implication: Demonstrates tolerability and early efficacy, supporting expansion into a randomized Phase II study (scheduled for 2027).

Practical Tips for Researchers Implementing ALCs

- Optimize lectin affinity – Use directed evolution to enhance thiên‑specific binding while minimizing off‑target lectin activity on normal tissues.

- Select complementary antigen targets – Pair lectin‑rich glycans with protein epitopes that are not down‑regulated after glycan removal (e.g., combine SNA‑based lectin with EGFR‑targeting mAb).

- Monitor glycan shedding – Serial mass‑spectrometry of serum glycoproteins can serve as a pharmacodynamic read‑out for lectin engagement.

- Combine with low‑dose checkpoint inhibitors – The “glycan‑unmasking” effect of ALCs synergizes with PD‑1/PD‑L1 blockade, allowing dose reduction and lower toxicity.

Potential Benefits Over Conventional Immunotherapies

- Broader tumor coverage: Glycans are less prone to mutational loss than protein antigens, reducing escape via antigenic variation.

- Enhanced innate immunity: Lectin binding activates complement and improves NK‑cell ADCC, providing a rapid first‑line attack.

- Reduced resistance: By dismantling the sialic‑acid shield, ALCs prevent Siglec‑mediated T‑cell inhibition, a major resistance pathway in chronic checkpoint therapy.

- Versatile platform: The modular design permits swapping mAb or lectin modules to address diverse cancer types (e.g., ALC‑HER2‑SNA for gastric cancer, ALC‑EGFR‑LTA for glioblastoma).

Regulatory and Manufacturing Considerations

- Glyco‑engineering compliance: GMP‑grade lectin production must meet FDA’s “Protein Therapeutics” guidance for impurity profiling and endotoxin limits.

- immunogenicity assessment: Conduct in silico T‑cell epitope mapping of lectin domains and perform ADA (anti‑drug antibody) monitoring in early trials.

- Stability:购彩平台 data indicate that lyophilized ALC formulations retain ≥ 90 % activity after 12 months at 2‑8 °C, simplifying cold‑chain logistics.

Future Directions & Emerging Research

- Bispecific ALCs: Next‑generation constructs that simultaneously target two glycans (e.g.,sialyl‑Tn and GD2) are undergoing pre‑clinical testing,showing additive immune‑reversal effects.

- Nanoparticle delivery: Encapsulation of ALC ਇਕ in biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles improves tumor penetration and reduces systemic exposure (ACS Nano, 2025).

- Artificial intelligence‑driven design: deep‑learning models predict optimal lectin‑protein interfaces, accelerating the discovery pipeline for new chimeric candidates.

Takeaway for Clinicians and Translational scientists

- Integrating antibody‑lectin chimera therapy can overcome the glycan‑mediated immune escape that limits many current immunotherapies.

- Early clinical data support a favorable safety profile and measurable anti‑tumor activity, justifying inclusion in combination regimens.

- Ongoing biomarker validation—particularly serum sialylation levels and CTC glycan profiling—will be essential for patient selection and response monitoring.

References available upon request; primary sources include Nature (2024), Cell Reports (2025), and the 2025 Phase I trial poster presented at the AACR Annual Meeting.