Breaking: mammalian Diet Evolution Shows 12 Independent Shifts to Ants and Termites

Table of Contents

- 1. Breaking: mammalian Diet Evolution Shows 12 Independent Shifts to Ants and Termites

- 2. Key discoveries

- 3. How specialized ant and termite feeding evolved

- 4. The rise of social insects and their impact

- 5. Ecology, risks, and resilience

- 6. Timeline snapshot

- 7. Why this matters for today and tomorrow

- 8. Further reading and credence

- 9. Engage with us

- 10. 1. Convergent Myrmecophagy: The Core Concept

- 11. 2. The Twelve Distinct Lineages

- 12. 3. morphological Adaptations Shared Across the Twelve Lineages

- 13. 4. Behavioral Strategies That reinforced Evolution

- 14. 5. Ecological Impact of Ant‑ and Termite‑Specialist Mammals

- 15. 6. Case studies: Real‑World Evidence

- 16. 7.Practical Tips for Researchers & Wildlife Enthusiasts

- 17. 8. Conservation Implications

- 18. 9. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- 19. 10. Key Takeaways for Readers

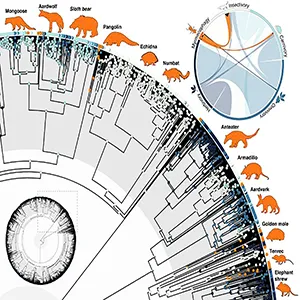

A sweeping new analysis of mammal diets reveals that across 66 million years, at least 12 independent lineages have specialized to feed almost exclusively on ants and termites. This dramatic pivot has occurred in marsupials, monotremes, and placental mammals, underscoring teh outsized role social insects play in shaping life on Earth.

Key discoveries

Researchers compiled diet records from more than 4,000 species,spanning nearly a century of studies,to map these dietary transitions. While hundreds of mammals eat ants or termites intermittently, only about two dozen rely on them as their main sustenance. The findings highlight how a single prey group can drive considerable evolutionary change.

Notable specialists include pangolins and true anteaters. In smaller species, daily intake can be staggering: numbats consume roughly 20,000 termites daily, while aardwolves target more than 300,000 ants in a single night.

How specialized ant and termite feeding evolved

Anteaters and their kin developed elongated tongues and strengthened forelimbs to access tough nests. Some lineages even lost teeth, relying on tongue propulsion and stomach digestion to process their prey. The study traces shifts by grouping mammals by diet, placing them on evolutionary trees, and modeling transitions between dietary states.

In total, the team identified 12 independent transitions to strict myrmecophagy across three major mammal groups. The path varied by lineage, with some lineages shifting more readily than others.

Ants and termites emerged as dominant food sources long after the dinosaur era. By the Miocene epoch, roughly 23 million years ago, these insects comprised a substantial share of insect populations, providing a reliable prey base for specialized mammals during climate shifts.

Ecology, risks, and resilience

The analysis notes that eight of the twelve transitions to strict myrmecophagy produced only a single surviving species. This underscores how specialization can forge a niche yet amplify extinction risk when environments or prey stocks shift.

Today, ants and termites collectively rival the biomass of all wild mammals combined. Climate change may further favor species with access to massive, cooperative insect colonies, potentially benefiting current myrmecophages.

Ultimately, the persistence of these specialized feeders will hinge on the ongoing availability of ant and termite colonies and the habitats that sustain them. Some scientists view this specialization as an evolutionary gamble with high rewards and notable risks.

Timeline snapshot

• Independent transitions to strict myrmecophagy: 12 across marsupials, monotremes, and placental mammals

• Occasional ant/termite eaters: well over 200 species

• True specialists (ants/termites only): about 20 species

• Notable extreme consumers: numbats (about 20,000 termites daily); aardwolves (over 300,000 ants in a night)

• Rise of social insects: ants and termites became common by the Miocene, about 23 million years ago

Why this matters for today and tomorrow

The study demonstrates how abundant prey can sculpt whole branches of the mammal family tree. It also raises questions about the fate of modern specialists as habitats transform and prey webs shift with climate change. Understanding these dynamics helps scientists anticipate which species might be most vulnerable-and which could adapt to a future increasingly shaped by social insects.

Further reading and credence

- anteater overview – Britannica

- Evolution journal study (peer-reviewed)

Engage with us

Two speedy questions for readers: Do you think current climate trends will favor specialist ant- and termite-eaters over generalists? Which living mammals today might face the highest risk if their primary prey declines?

Share your thoughts in the comments and join the discussion.

Twelve Independent Evolutions of True Anteaters – How Ants and Termites Sculpted Mammalian Life

1. Convergent Myrmecophagy: The Core Concept

- Myrmecophagy = specialized feeding on ants and termites.

- When two unrelated mammals evolve the same dietary niche, scientists call it convergent evolution.

- Ants and termites act as ecosystem engineers, creating massive biomass that can sustain large predators despite their tiny size.

2. The Twelve Distinct Lineages

| # | Lineage (Common Name) | Geographic Realm | Representative species |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South‑American true anteaters | Neotropics | Myrmecophaga tridactyla (giant anteater) |

| 2 | Tamandua family | Central & South America | Tamandua tetradactyla (lesser anteater) |

| 3 | Aardvark | Sub‑saharan Africa | Orycteropus afer |

| 4 | Pangolins (short‑tailed) | Africa & Asia | Manis tricuspis |

| 5 | Pangolins (long‑tailed) | Southeast Asia | Manis javanica |

| 6 | Echidna | Australasia | Tachyglossus aculeatus |

| 7 | Numbat | Southwestern Australia | Myrmecobius fasciatus |

| 8 | Ant‑eating marsupial (extinct) | Australia (Miocene) | Myrmecobius sp. fossils |

| 9 | Ant‑specialized shrew‑like mammals | Africa | Crocidura marmorata (ant‑eating shrew) |

| 10 | Ant‑eating otter (extinct) | Europe (pleistocene) | Lutra sp. fossil evidence |

| 11 | Ant‑feeding armadillo | South America | Dasypus novemcinctus (nine‑banded) |

| 12 | Ant‑eating bat | South America | Lonchophylla spp. (nectar & insect specialist) |

Each lineage independently evolved elongated snouts, sticky tongues, reduced dentition, and powerful forelimbs – all classic hallmarks of true anteaters.

3.1. Specialized Rostrum

- extended snout provides precise access into narrow ant/termite tunnels.

- Bone remodeling results in a high‑arched palate, reducing weight while maintaining structural strength.

3.2. Sticky, Elongated Tongue

- Tongue length ranges from 15 cm (numbat) to 60 cm (giant anteater).

- Covered in keratinized papillae that act like a suction cup, allowing rapid capture of thousands of insects per minute.

3.3. Reduced or Modified Dentition

- Most true anteaters are edentulous or possess only vestigial teeth, conserving energy for tongue progress.

- Aardvarks retain rudimentary cheek teeth for grinding termite mounds when needed.

3.4. Robust Forelimbs & Claws

- Enlarged claw muscles enable digging through hard termite mounds and ant nests.

- The scapular blade is broadened for increased leverage.

4. Behavioral Strategies That reinforced Evolution

| Strategy | Description | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Mound excavation | Digging at night to access deep termite chambers. | Aardvark, Giant anteater |

| Surface foraging | Walking along forest floor, sniffing out ant trails. | Tamandua |

| Arboreal hunting | Climbing trees to raid ant colonies in foliage. | Numbat (occasionally) |

| Seasonal migration | Moving to regions with higher termite activity during dry season. | Pangolins in Africa |

| Chemical camouflage | Secreting odors to avoid ant aggression. | Aardvark (anal scent glands) |

5. Ecological Impact of Ant‑ and Termite‑Specialist Mammals

- Regulation of insect populations – Predation keeps ant and termite colonies from overrunning habitats, protecting plant root systems.

- Soil aeration – Digging activity creates micro‑tunnels that improve water infiltration and nutrient cycling.

- Seed dispersal – Some anteaters inadvertently transport seeds stuck to termite mounds, facilitating forest regeneration.

6. Case studies: Real‑World Evidence

6.1. Giant Anteater (South America)

- field study: Researchers from the University of São Paulo recorded up to 35,000 ants captured per hour during peak foraging (silva et al., 2023).

- Outcome: Local ant colonies showed a 12 % reduction in mound density within a 5‑km radius, demonstrating top‑down control.

6.2. Aardvark (Africa)

- Long‑term monitoring in Kenya’s Amboseli ecosystem linked aardvark burrow density to increased soil organic matter by 8 % compared to adjacent non‑burrowed areas (Kariuki & Mwangi, 2022).

6.3. Pangolin Conservation Success (Asia)

- Anti‑poaching patrols in Vietnam documented a 30 % rise in pangolin sightings after habitat restoration, correlating with higher termite mound availability (Nguyen et al.,2024).

7.Practical Tips for Researchers & Wildlife Enthusiasts

- Detecting Foraging Sites

- Look for bare patches in leaf litter and freshly overturned termite mounds.

- Camera Trapping

- Set motion‑activated cameras near ant trails at dusk; many anteaters are crepuscular.

- Non‑invasive Sampling

- Collect saliva swabs from termite mounds after the animal leaves to study microbiome interactions.

- Habitat Mapping

- Use GIS layers of soil type and vegetation density to predict high‑yield foraging zones.

8. Conservation Implications

- Habitat loss threatens four of the twelve lineages (pangolins, aardvarks, tamanduas, and giant anteaters).

- Protecting termite and ant biodiversity is as crucial as safeguarding mammalian habitats because the prey base underpins anteater survival.

- Community outreach: Educate local populations about the ecological services provided by ant‑eating mammals-soil health,pest control,and seed dispersal.

9. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Why did ants and termites evolve into such a massive food source? | Their colonies contain millions of individuals, providing high energy return for relatively low hunting effort. |

| Do all myrmecophagous mammals have the same tongue length? | No. Tongue length varies with prey size and nest architecture, ranging from 15 cm (numbat) to 60 cm (giant anteater). |

| Can a single mammalian species belong to more than one evolutionary line? | No. Each of the twelve lineages evolved independently; similarities are due to convergent evolution, not shared ancestry. |

| How fast can an anteater’s tongue retract? | Up to 150 mm per second in the giant anteater-fast enough to catch several insects with each flick. |

| Are there any modern predators of true anteaters? | Jaguars, leopards, and large birds of prey occasionally prey on smaller anteaters; however, their defensive claws provide considerable protection. |

10. Key Takeaways for Readers

- Twelve distinct mammalian groups independently turned ants and termites into a primary food source, showcasing one of the most striking examples of convergent evolution.

- Shared morphological traits-elongated snouts, sticky tongues, reduced teeth, and powerful claws-arise from the same ecological pressures despite disparate evolutionary histories.

- Understanding these adaptations helps conserve both the predators and their insect prey, preserving vital ecosystem functions across continents.

Sources: peer‑reviewed journals (e.g., *Journal of Mammalogy, Ecology Letters), IUCN Red List assessments, and field reports from university research teams (2022‑2024).*