The Spanish doctor Francisco Hernández set sail in 1570 from an old world that believed in fantastic creatures, such as the unicorn and sea monsters, and returned seven years later with colorful drawings of even more amazing beings, which also existed: the armadillo, the macaw, The toucan. Hernández, born in La Puebla de Montalbán (Toledo) around 1515, had led the first scientific expedition to the New World. His paintings were so impressive that they ended up decorating the chambers of King Philip II, but all of them burned in the fire of the Monastery of El Escorial in 1671 or were lost to oblivion, until another Spanish doctor, Germán Somolinos d’Ardois, arrived at Mexico fleeing the Civil War in 1939 and stumbled upon the elusive trail of America’s first scientific explorer.

Philologist Helena Rodríguez Somolinos remembers that, at the end of 2022, she opened a closet and began to gossip about the boxes inherited from her parents, now deceased. There was the archive of her uncle Germán, who died in Mexico City in 1973. There were manuscripts, photographs, letters, even locks of hair. It was unpublished material that allowed us to follow the steps of Germán Somolinos through Mexico in the 20th century, but also those of Francisco Hernández almost 400 years earlier. They were two intertwined stories. “My sister Victoria and I spent Christmas completely abducted, it was incredible,” recalls the niece, an expert in classical Greek at the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC).

Germán Somolinos, born in 1911 in Madrid, studied Medicine in the capital and was caught almost immediately by the Civil War. He was 25 years old and was a member of the Socialist Youth. He worked as a doctor in the Republican aviation, shrapnel embedded in his back, he went through a concentration camp in France and embarked on the path of exile to Mexico, from where he never returned. There he became obsessed with the legendary scientific expedition of Francisco Hernández, of which hardly any traces remained. His niece shows a typewritten letter sent by Somolinos in 1948 to his Madrid family: “Another order: Francisco Hernández was from La Puebla de Montalbán and was born around 1520, could you find me descriptions of that town that are closest to the time?” .

The Toledo town, on the bank of the Tagus, then dominated a Castilian manor of olive trees and cereals. The writer Fernando de Rojas was also born there, author in 1499 of The Celestine, a work that shows spells with viper venom, wolf eyes and bat blood. The powerful Cardinal Pedro Pacheco was also born in the town, who was three votes away from being Pope in 1559 after virulently defending, at the Council of Trent, the immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary. Francisco Hernández grew up in that environment of faith and superstition.

At the age of 15, the man from Toledo went to study Medicine at the University of Alcalá de Henares. He learned anatomy from the best book—dissected human corpses—and entered the Court in 1567, as physician to Philip II. Two years later, the king entrusted him with an unprecedented mission: to travel the New World on a mule to identify all the medicinal plants. The monarch ordered him to embark on the first fleet that left for America. “You must inform yourself wherever you go of all the doctors, surgeons, herbalists, Indians and other curious people in this faculty and who you think will be able to understand and know something,” ruled Philip II.

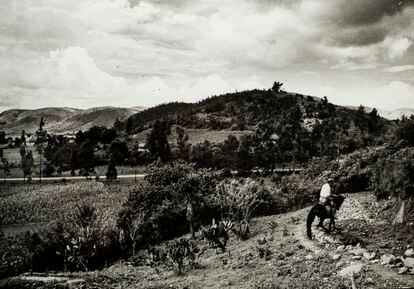

Hernández sailed from Seville in August 1570 bound for New Spain, present-day Mexico. The fleet docked in the port of Veracruz six months later. For six years, Hernández toured the territory accompanied by local painters, scribes, mule drivers and even a cosmographer. The doctor was more ambitious than his king. “It is not our purpose to give an account only of the medicines, but to review the flora and compose the history of the natural things of the New World, placing before the eyes of our countrymen, and mainly of our Lord Felipe, everything that is produced in this New Spain,” he wrote.

One day in March 1577, sick and tired at the age of 62, Francisco Hernández began his return, with the fruits of the first scientific expedition in America. He carried with him almost 70 bags of seeds and roots, eight barrels of medicinal herbs and 22 volumes of manuscripts and colorful paintings of plants and strange creatures of the New World. Germán Somolinos narrated the epic for the first time in his monumental Life and work of Francisco Hernándezpublished in 1960 by the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Somolinos’ family has donated his archive to the CSIC. Historian Leoncio López-Ocón and his colleagues Teresa López and Irati Herrera have been analyzing the documents for a year. “It is a treasure. Somolinos is one of the greats in the history of medicine, but the fundamental thing is what he did with Francisco Hernández: it is a historiographic monument. Somolinos is fascinating and Hernández is fascinating,” López-Ocón celebrates.

Teresa López, 24, has dedicated an erudite final degree project in Humanities to the intersecting stories of the two Spanish doctors in Mexico. “Somolinos portrayed himself when telling the story of Hernández,” she believes. “Somolinos’ research work is motivated by a desire to reconquer the Spanish intellectual movement from oblivion and fascism that pushed him into exile,” she points out in her work for the Carlos III University of Madrid.

Francisco Hernández toured present-day Mexico with local painters, including Pedro Vázquez, Antón and Baltasar Elías, whom he mentioned in his will so that they would be rewarded as they deserved. His idea was to publish his work in Latin, Spanish and Nahuatl, the majority language in the territory. Somolinos highlighted this miscegenation, “a cultural amalgam in which indigenous elements infiltrate the dominating mentality, modifying it in many aspects.” In his opinion, “in the medical history of humanity, it may be the only occasion in which a cultural phenomenon of such significance and without the possibility of being repeated has occurred.”

Hernández enriched world medicine by describing the medicinal plants of the New World, but when he finally crossed the ocean back, his work was mistreated. King Philip II had already displeased him with his supposed slowness in traveling around America on a mule. “This Doctor has promised many times to send the books of this work, and he has never fulfilled it: to send them safely in the first fleet,” ordered the monarch in 1575. Hernández, surprisingly, responded by dragging his feet. He asked for more time because he was experimenting with the plants on sick people and translating his writings into Nahuatl, “for the benefit of the natives.” And he said goodbye saying: “Humble vassal and servant of Your Majesty that the Royal hands of his kiss.”

Upon his return, Hernández and his 22 manuscript volumes of the Natural History of New Spain They were despised by the king. Philip II commissioned another doctor, the Neapolitan Nardo Antonio Recchi, to summarize all the material in a less ambitious work. Recchi amputated the original, ignoring Hernández’s miscegenation, and returned with a copy of his manuscript to Naples in 1589, two years after the Toledo native’s death.

The historian Juan Pimentel tells in his book Ghosts of Spanish science (Marcial Pons publishing house, 2020) that the astronomer Galileo Galilei himself was able to contemplate the Hernandine drawings of the plants of the New World, copied over and over again in Italy: “They must have seemed so extravagant that he questioned their own existence.” Many of Hernández’s manuscripts burned in El Escorial in 1671 or remain hidden in some archives. Pimentel believes that he is “the patron saint of the ghosts of Spanish science,” because “the destiny of his colossal work vanished.” Teresa López paraphrases Pimentel: “Francisco Hernández is the biggest ghost in the history of Spanish science.”

You can write to us at [email protected] or follow MATERIA in Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or subscribe here to our bulletin.

to continue reading

_

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/AW2KNQ2UOZA4PHPLO4DEKRFIOQ.jpg?fit=768%2C591&ssl=1)