“Velasco became very ill shortly after arriving, they took him off the field and we have not heard from him again, most likely he was gassed. Blasco died on December 18 and Amer, in February, both because they lost morale and spirit and that was his downfall; Salavera died in January consumed by diarrhea, lice and mistreatment; Marín died in February of typhus, and Redondo, on the night of March 8 to 9, of fever, lice and, above all, hunger; We slept together and he died hugging me, talking to me about his children. I spent the entire night from 11 o’clock with the poor corpse and at dawn, helped by another Spaniard, we were able to wash it and tidy it up a little before they took it away. I live by miracle, but I live…”

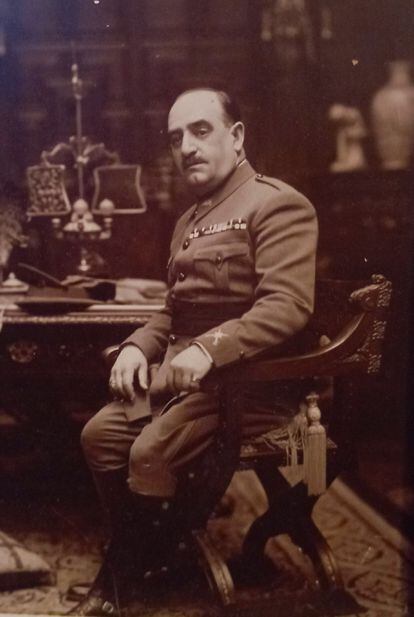

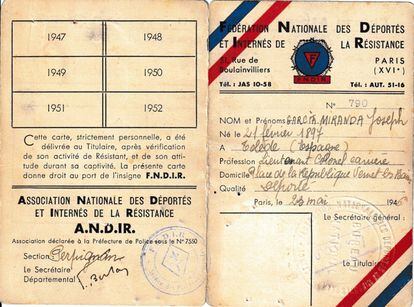

Lieutenant Colonel José María García-Miranda, 48, writes to his wife, Lucía, on May 2, 1945 after being liberated by the Americans from the Nazi concentration camp in Dachau (Germany). He weighs 39 kilos and it will take him a while to be reunited with her because her survivors are so weak and sick that they have to undergo quarantine. The letter summarizes the end of the tragic fate of a group of leaders and officers of the Republican Army who, in 1939, once the Civil War was lost, crossed into France and, like thousands of civilians, stumbled through detention centers until end up in one of the branches of hell, the cruel seats of the holocaust. García-Miranda’s great-nephew, Rafael Pañeda Reinlein, found years ago, in an attic loft, inside a suitcase, his great-uncle’s texts and, with his sister Iciar, began to pull the thread to find out who they were. those men you talked about in your letter. Rafael remembers the emotion when he opened those “brown-covered notebooks that had been silent for so long. The newly liberated letters from Dachau are a monument,” he states. The result is an exciting story of loyalty, honor and camaraderie in the most difficult circumstances, collected in the book The Vernet Eight, for this French town being the first stop on his journey after losing the war. Published by the Ministry of Defense, the work serves as a well-deserved tribute. The initiative, like that of the State Attorney General’s Office, which recently published In memory of Javier Elola, a prosecutor who was shot, aims to recover a forgotten story: that of the public servants who paid with everything for their defense of democracy, including their own blood. Two of the sons of these soldiers were murdered by men who said they supported the side in which their parents were fighting, that of the Republic.

Iciar and Rafael Peñada are nephews of another of the great names of democracy, Fernando Reinlein, a member of the Democratic Military Union (UMD), the clandestine group of soldiers who monitored, from within the Army, so that the dictatorship was not perpetuated. “I work in the Ministry of Defense,” explains Iciar, “and when I say the last name Reinlein, some make a gesture for the UMD, and others say: ‘Ah, but you are also the granddaughter of a military medal,’ because my grandfather was in the Blue Division [unidad española de apoyo a los alemanes en la II Guerra Mundial]. “This situation, of relatives on both sides, occurs in many military families.”

The detention

On December 8, 1943, the Gestapo detained eight Republican soldiers at the Alexandra Hotel in the French town of Vernet les Bains: General Mariano Gámir Ulibarri, 66 years old; Colonels Jesús Velasco Echave (65); Carlos Redondo Flores (64) and César Blasco Sasera (66); lieutenant colonels Fernando Salavera Camps (60) and José Mª García-Miranda Esteban-Infantes (46) and commanders Joan Amer Vadell (46) and Teodoro Marín Masdemont (66). Like the rest of the Republican Army, they have different ideas and origins. Gámir was born into a military, Catholic and monarchical family. On April 14, 1931, when the Republic was proclaimed, according to a biography written by Manuel Amores Torrijos in collaboration with the family, he expressed his “distress at lowering the red flag for the last time.” The coup of July 18, 1936 caught him in Valencia. The next day he sends a telegram to President Azaña to express his loyalty. “The decision was not easy due to the militancy in Falange of three of my children,” it is recalled in the book. One of them, Pepe, 26 years old, was murdered in August 1936 by a “group of leftists” who took him out of the Huete prison (Cuenca) to kill him “taking justice into his own hands.” General Gámir then states: “The family tragedy made a feeling of guilt take over me in the first days of mourning, assailing me with doubts as to whether I had chosen the wrong side.” In November 1936, his nephew José María was also murdered in Paracuellos: “My desperation reached the limit…”.

What affects the most is what happens closest. So you don’t miss anything, subscribe.

Colonel Velasco was the son and grandson of soldiers and had taught at the Toledo Academy, as stated The Vernet Eight, “to a young cadet named Francisco Franco Bahamonde.” In November 1936, his son Antonio was also murdered in Paracuellos. Redondo’s parents were teachers.

After the arrest at the Alexandra Hotel, the group is taken to a prison in Perpignan, accused of “clandestine resistance, collaboration with the maquis, aid and accommodation for the resisters and dissemination of clandestine newspapers,” according to a letter from the head of the resistance of Vernet les Bains, Pierre Vidal, registered in the French Defense Historical Service. Two months later, they were handed over to the French police and their conditions improved significantly. The day before they are transferred to the Vernet d’Ariege concentration camp, 20 kilometers from Toulouse, Gámir suffers an attack and loses his sight and consciousness. The doctor who treats him issues a certificate to admit him to the hospital and offers his colleagues to process a similar document. The group debates whether or not to accept the offer and finally, Colonel Velasco decides that it is too risky because if the Germans become suspicious they may force the delicate Gámir to leave the hospital and make the trip with them. Seven are sacrificed for one. The decision marks a before and after: only one of them will save their life.

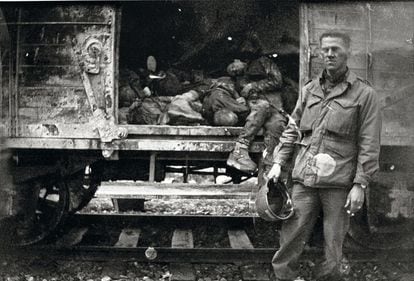

On June 30, 1944, the group, now numbering seven, is transferred to Dachau. The journey is made in cattle cars where the prisoners are so crowded that they have to take turns sitting. The convoy transports about 700 deportees, including 70 Spaniards. García-Miranda tells in his diaries how some manage to escape: “They achieve it in an amazing way, lifting the ground, getting down and letting the train pass over them, cowering.” On August 28, almost two months later, they arrived at the work camp, now converted into an extermination center.

Velasco, contrary to what García-Miranda explained in the letter to his wife, was not gassed. As he had arrived at Dachau very ill, they sent him to the Bergen-Belsen camp, where he met Anne Frank, and there he died, like the girl in the famous and sad diary. Meanwhile, the rest of the group, now numbering six, tries to survive in Dachau, where every morning the guards line up their prisoners to select those who can continue working and send those who are already too weak to the gas chamber. . Colonel García-Miranda comes to act as a guinea pig in a medical experiment. Only he and Gámir, who had stayed in the hospital, will be able to tell what happened.

In 1948, Gámir reunites in Paris with his son Alfonso, a Falangist, who reproaches him for having fought “with the communists,” according to the book. The general responds that he cannot understand “what a promise of fidelity, the concept of honor, means to a soldier.” “My father,” says Alfonso Gámir, “was very close to José Antonio Primo de Rivera. He had different ideas than my grandfather, but they never lost affection, that’s why he went to look for him in France.” The general had been condemned in Spain, in his absence, for military rebellion. “It was just the opposite: those who had rebelled were the Francoists, but they won the war.” “They went from defeat to defeat,” adds Iciar Pañeda, “until the final defeat.”

In 2015, the then French Prime Minister, Manuel Valls, dedicated a state pardon to the Spaniards who, like the Vernet Eight, ended up in their country after Franco’s victory and, in many cases, helped free it from the Nazis: “They were humiliated. They wanted to take away their dignity. Those who fled in search of freedom expected another type of reception. That’s not France,” he said. García-Miranda and Redondo had a certificate of Resistance activities. Both in Spain and France they fought against the same enemy.

to continue reading

_