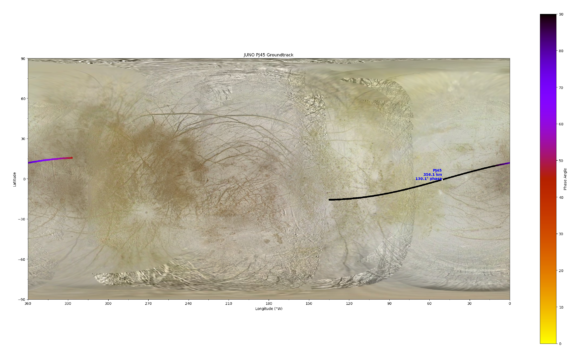

Behind the Ganymede flyby by the Juno probe last June 2021, all of us, starting with a server, were amazed at the quality of the images obtained by the modest JunoCam camera. Now the NASA probe destined to study the interior of Jupiter has made the closest flyby of a Jovian satellite that it will carry out in the remainder of the mission. On September 29, 2022 at 09:36 UTC, Juno passed just 358 kilometers from the surface of Europa taking advantage of the passage through perijovian number 45 (PJ45). It is the closest encounter with this moon of Jupiter since the Galileo probe passed 351 kilometers on January 3, 2000. Of course, Galileo obtained higher resolution images thanks to its more powerful cameras since its speed was not so high. And it is that Juno has zoomed past Europa at nothing more and nothing less than 23.6 km/s.

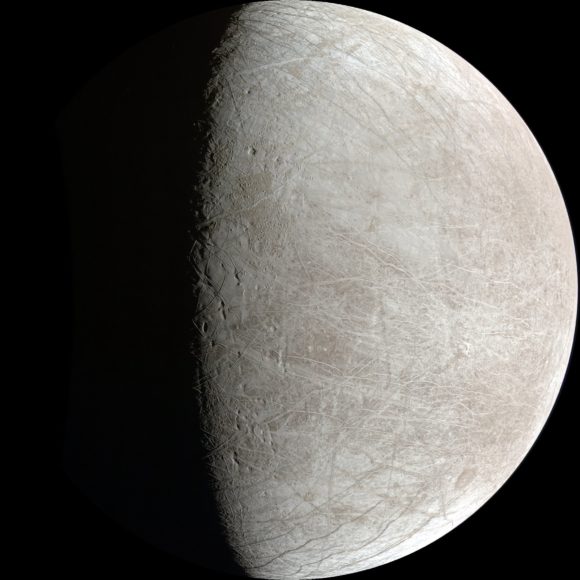

Despite everything, the images are certainly amazing. Chance has wanted that, in addition, Juno has photographed in detail an area of the moon that had been seen in low resolution by Galileo, the so-called Annwn Regio (the name comes from Annwn, the world following death in Welsh mythology). Although the presence of the ocean under the crust makes the surface of Europa very young, it does not change that much in such a short time, but you can join the thousands of professional and amateur experts who are comparing these images with those taken by Galileo in search of of some change in these two decades. It’s chilling to think that Juno was regarding to be launched without the JunoCam camera, which was only added at the last minute so as not to contravene the new rule that every NASA probe had to carry some kind of camera, even if it was just as an exercise in ” public relations”. Because let’s not forget that JunoCam, despite the spectacular nature of its images, is not a scientific instrument of the mission and it is the amateur community that is responsible for processing and publishing the images.

In the images of Juno, the lines that cover the European surface can be seen, divided into lines y ditches, and that have been produced by the tensions and compressions of the icy crust. In fact, although this is Juno’s first close flyby of Europa, the spacecraft had already passed within regarding 50,000 and 90,000 kilometers of the satellite regarding a year ago during two far passes. Unfortunately, it will be the last, as Juno continues to change the latitude of its perikhovium as it orbits Jupiter in order to analyze higher latitudes on the planet. Now we will have to wait at the end of 2023 and 2024 for Juno to approach regarding 1,500 kilometers from Io, the world with the most volcanic activity in the solar system.

Europa is a fascinating world due to the more than probable existence of a subterranean ocean under the outer crust of ice and, at the moment, it is one of the places with the greatest astrobiological potential outside of Earth. In the next decade, Europa will be studied by NASA’s Europa Clipper mission and, to a lesser extent, by ESA’s JUICE probe and China’s Tianwen 4. Unlike other ocean worlds in the solar system, Europa’s ocean is believed to be in contact with the hot, rocky interior of the moon, increasing the likelihood that life has arisen, while also being in direct contact. with the surface, which allows its study from the outside thanks to the analysis of the composition of the surface ice. Unfortunately, Juno lacks spectrometers and other scientific instruments to study the composition of Europa’s ice in detail, so we will have to wait for Europa Clipper. In recent years, the biggest mystery in Europe is the possible existence of geysers.

If so, its ocean might be studied in a much simpler and more precise way from the outside. Although there is evidence that water vapor and other substances are expelled from the surface, it has not been possible to confirm that they are actual geysers, such as on Enceladus. In this sense, Juno’s plasma sensors may give some limited information regarding the mystery of the geysers, while the magnetometer may provide new information regarding the interior of this moon. Similarly, the MWR (Microwave Radiometer) instrument will be able to offer us a new view of the temperature of the icy crust. After this flyby, Juno will continue to circle Jupiter every 43 to 38 days in order to study the interior of Jupiter, which is its primary mission. The last orbit of the current extended Juno mission will take place in September 2025. In any case, these images are a small appetizer of what awaits us with Europa Clipper. The wait is going to be very long!

Thanks to @NASAJunothere’s a new image of #Europa that has gotten me super jazzed regarding science. Just what I needed today! Here are some side-by-sides I put together of Galileo/Voyager mosaics (left) and the new Juno data (right). pic.twitter.com/OCECUvycpU

— Alyssa Rhoden (@aRhoDynamics) September 30, 2022