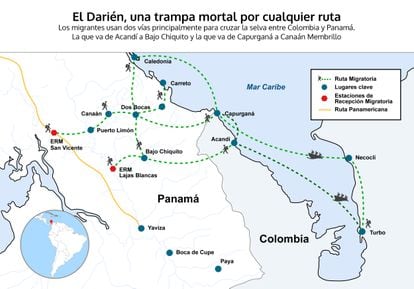

Rose Mary and Jean Carlos have been sleeping for two months in a tent on the shore of the Colombian Caribbean Sea. They survive there with their two ten-year-old twin children and their dog Candy. They are Venezuelans. They arrived at the beaches of Necoclí, Antioquia, with their lives packed in a few suitcases. Their first objective – like that of thousands of migrants of different nationalities who camp with them – is to take a boat that will take them to Capurganá or Acandí, on the other side of the Gulf of Urabá. There the thick Darién jungle awaits them. They must walk for three days until they reach the border with Panama. Then they have a long, expensive and very dangerous road ahead of them to the United States. Until December they lived in Piedecuesta, Santander, near Bucaramanga, more than 700 kilometers away from Necoclí. There they recycled, fixed up apartments and cooked at private dinners and elegant hotels. They abandoned everything for “the American dream.”

In 2023, more than 457,000 people crossed that border on foot, according to information from the Government of Panama and Human Rights Watch. Almost double the 248,000 that passed through there in 2022. Although there are no exact calculations for 2024, the local authorities of Urabá estimate that every day there is a flow of between 1,000 and 2,000 migrants, concentrated in the ports of Necoclí and Turbo, in the Atlantic. With an aggravating factor: many cannot continue on their way immediately due to economic difficulties, security problems or because the boats cannot cope. Like Rose Mary and Jean Carlos, thousands of Venezuelan, Peruvian, Ecuadorian, Haitian, Cuban, Chinese or Afghan families remain stranded in Necoclí for weeks or months. They endure hunger, suffer from illnesses and suffer violence while they raise money to cross the jungle.

Newsletter

The analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your mailbox

RECEIVE THE

The past week was particularly difficult in Necoclí. On Thursday, February 22, the Police and the National Navy captured the captains of two boats for crimes related to migrant trafficking. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, the high-speed ships transported 151 migrants “illegally and in precarious security conditions.” Shipping companies ceased operations in protest. That generated a massive damming. The migrants continued to arrive at the usual pace, but they could not continue on their way. About 5,000 people gathered on the beaches. Food, drinking water, and camping space became increasingly limited. The humanitarian situation became extreme.

Secretary Wachert says he does not know about the Clan’s intervention in migrant trafficking: “We have not had direct knowledge or contact with these organizations. We cannot validate it because we do not know at what point in the chain it happens.” However, the Ombudsman’s Office published a report in 2023 confirming that this criminal organization has all the power in the area and handles drug trafficking and migrant smuggling.

While illegals and some local businessmen get rich, migrants live in misery. Among them are three trans women who, in addition to the pain of leaving their home and poverty, have suffered discrimination. The evangelical churches, which sometimes give food to the migrants, ignore them: “When we get to the line they say that the lunches are over,” says one of the three Venezuelan friends who braid the hair of other migrants to complete the travel money. “We are here for the American dream, to have surgery,” she says. Rose Mary and Jean Carlos have helped them. They visit them, they lend them things to cook with, they do not discriminate against them.

The migrant couple takes turns working all day and all night. They sell coffee, candy and cigarettes. Every peso they earn, they save to complete the 990 dollars they must pay to ensure that the five reach the border (it is 330 dollars per adult and 165 per child). Candy, the dog, is also going to cross the jungle in a special bag. “We are missing 400 dollars,” says Jean Carlos with enthusiasm.

Next to Rose Mary and Jean Carlos’s family tent lives Carmen Rosalía Rojas, perhaps the oldest person among all the migrants gathered on the beach. She is 64 years old, has a couple of faded tattoos and she is the adoptive grandmother of a group of 23 Venezuelans who have been migrating from Chile. She dances, sings and runs on the beach. “I want to go to the United States to see something new. I already know all this. I have been to Ecuador, Peru, Medellín and Bogotá,” she recalls. Albert Díaz, one of the Venezuelans who is with her, says that they found her at a gasoline pump in Bogotá. “He was begging for money, selling candy. We saw her crying because her grandchildren had abandoned her and we told her to stay with us.” That was about a month ago and now they look like family. Albert carries Rosalía’s bag with the documents, doesn’t let her work and says that they are going to spend the Darién jungle together. “I promised her that I was going to come to the United States with her.”

It is Thursday afternoon and the news that the boats will operate again the next day spreads quickly among the tents. Some migrants feel joy because the dream of reaching the other side seems closer and closer. Others are distressed because they have not yet gotten enough money. Everyone is afraid of the jungle. The organization Doctors Without Borders has reported this week an increase in attacks suffered by the migrant population while passing through Darién. “In recent weeks, health teams have recorded more attacks of extraordinary violence and sexual violence, in an unprecedented number of assaults, in what is feared could be a worsening of the already terrible situation on the jungle route,” states in a report. In just one week in February, its medical teams treated 113 victims of sexual assault, including nine minors.

The night falls. Amid the difficulties, the migrants have built a large family on the beach. “We are in hell, but accompanied,” says one of them, and smiles. They make a bonfire. They cook pasta with tomato sauce and distribute it to everyone nearby. One is a young man who dreams of being a rapper in Harlem. His stage name is Turbo. He sings while he shaves and cuts the hair of his friends. It doesn’t matter that until recently they didn’t know each other, now they are family, they know that solidarity is the only way to make tragedy more bearable.